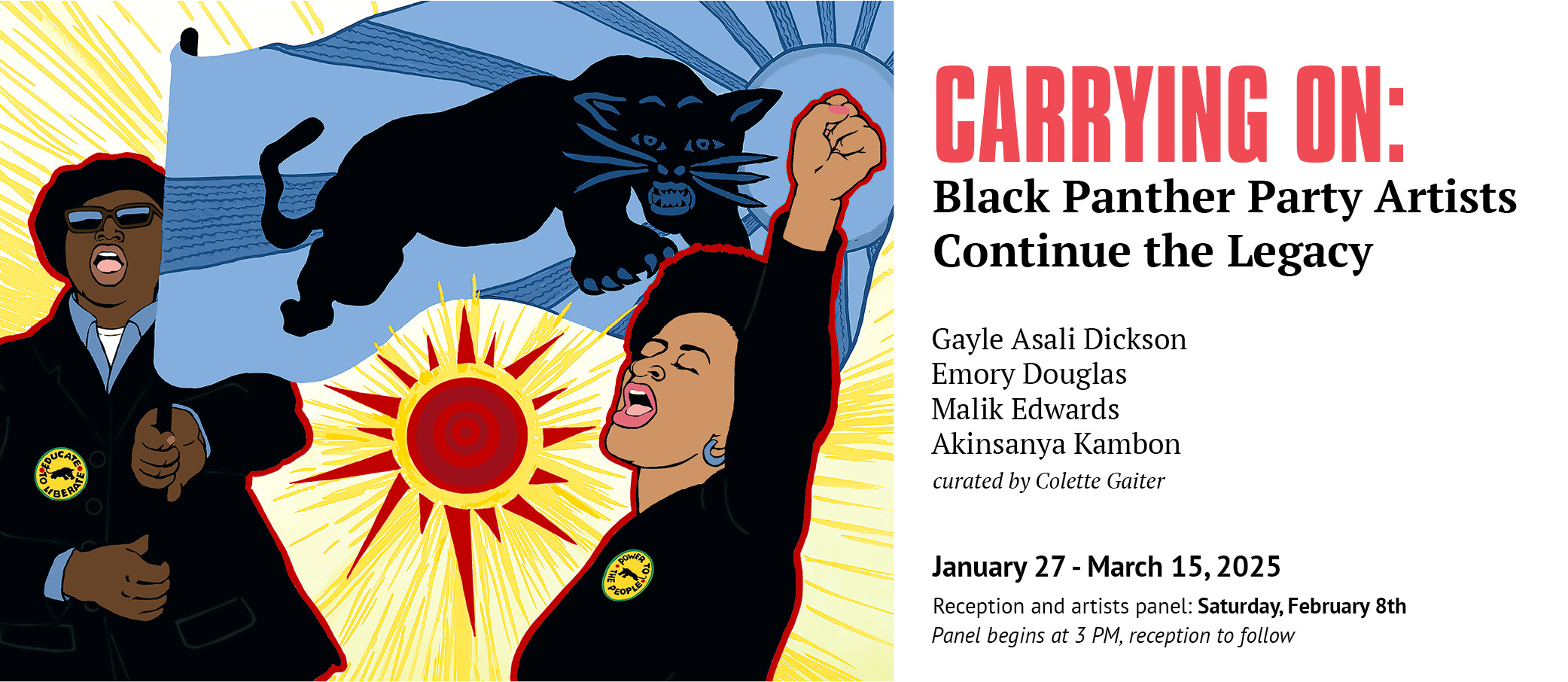

Carrying On: Black Panther Party artists

Carrying On: Black Panther Party artists

Carrying On: Black Panther Party artists continue the legacy

Gayle Asali Dickson

Emory Douglas

Malik Edwards

Akinsanya Kambon

Curated by Colette Gaiter

January 27 - March 15, 2025

301 High Street Gallery

These four artists were teenagers and young adults when the Civil Rights Act of 1964 ended legal segregation and discrimination in the United States. They grew up in the Jim Crow era, restricted by laws and practices that affected every aspect of their lives and severely limited opportunities to pursue their dreams. Through talent, perseverance, and serendipity, they became and remain artists.

The Black Panther Party and The Black Panther newspaper are the common denominators of their early artistic careers. Emory Douglas worked on the newspaper for 13 years—the others for much shorter periods. Their early illustrations and cartoons show Black people in ways that had never been seen in mainstream media or even the Black press.

In the decades since working on the BP newspaper, each artist expanded their ways of using figures to represent realities and communicate aspirational ideas. Drawings, paintings, clay sculptures, graphic design, digital prints, and images generated from Artificial Intelligence (AI) prompts fill the gallery. Two embroidered tapestries sewn by Zapatista women in Chiapas, Mexico, represent Emory Douglas’s numerous international collaborative projects.

Carrying On presents the artists’ lifelong commitments to people, justice, liberation, and the freedom to express their creative visions.

Carrying On gallery timeline with sources

'Carrying On: Black Panther Party Artists Continue the Legacy' on View Through March 15, 6abc

When Culture is a Weapon: Black Panther Artists Illustrate Truth, JerseyArts.com

Rowan’s Latest Art Exhibition Depicts Works Of Former Black Panther Party Artists, Follow South Jersey

Former Black Panther Party artists preserve history, Rowan Today

Spotlight, South Jersey Magazine

Black Panther Party artists unite in "Carrying On" exhibition at Rowan University, Art Daily

Rowan Art Gallery and Museum presents "Carrying On: Black Panther Party Artists Continue the Legacy", The Whit

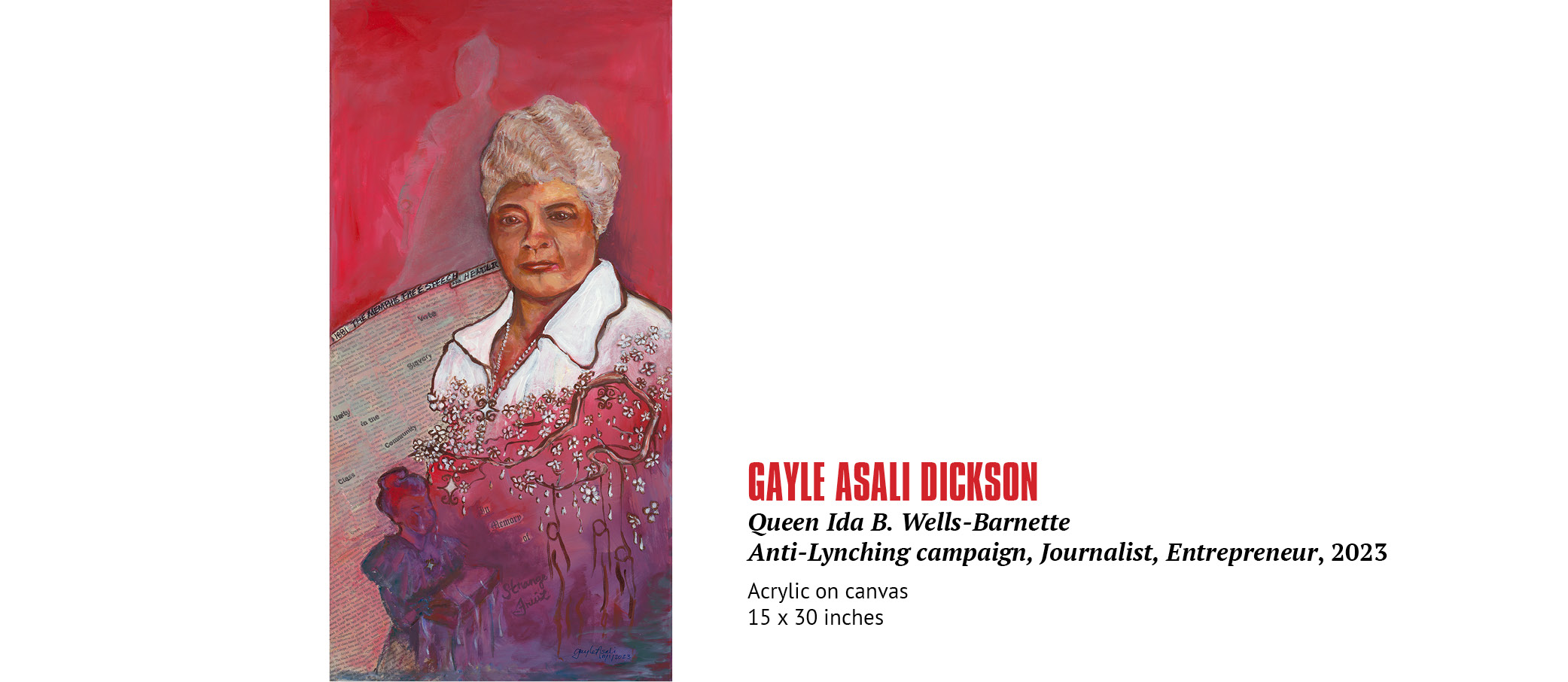

GAYLE ASALI DICKSON

Bio

The Reverend Gayle Asali Dickson is a San Francisco Bay Area native, an artist, a member of the Black Panther Party, and an ordained minister in the United Church of Christ denomination. In 1970, she joined the Black Panther Party in Seattle, and in 1972, she and other Seattle members migrated to the Oakland headquarters. Dickson was the only woman artist for The Black Panther newspaper between 1972 and 1974, drawing primarily women and children during the “Oakland Base of Operation” period. Between 1974 and 1976, she taught at the Oakland Community School using art as a teaching tool. After ordination in 1998, she served as Pastor of a church in South Berkeley for eight years. She started the Friday Night Art and Dinner Program, exposing children to world cultures through art and food. Her Little Bobby Hutton Youth and Adult Literacy Program at the church used The Black Panther newspaper as a teaching tool. Over the years, she continued her creative work, exhibiting in the Bay Area and nationally. Currently, she is working on a painting project about six women called “The Empowering Voice of Women from the Bible and African-American Women in History.”

Artist Statement

As an artist, I believe in my calling to help make sure that our African American stories, America’s stories, are not forgotten. Paintings like the ones of Queens Ida B. Wells-Barnett and Ella Baker remind us that Black history is America’s history. Queen Ida was an investigative journalist and an anti-lynching crusader. Queen Ella was an organizer and strategist during the U.S. Civil Rights Movement. Through a process I call “Spirits Revealed,” some of my paintings reveal themselves without a plan. The subject may be something I have been feeling some emotions about, as in “Stand…” created in the aftermath of George Floyd’s murder in 2020. The woman confronting dangerous spirits revealed itself as I randomly applied paint to paper. The portraits are part of a “Protest” series, echoing my work in the Black Panther Party. A postcard series updates issues that were social concerns in the 1970s. I recently added West African Adinkra symbols, such as “Gye Nyame,” to my paintings, representing Black Americans’ strong connections to the continent. Symbols appear in jewelry, integrated into clothing, or in other places in the work. The mandala drawing represents my efforts to connect with my African ancestors, which is essential for maintaining strength and power. Thank you, and I wish you blessings no matter where you are on your life’s journey.

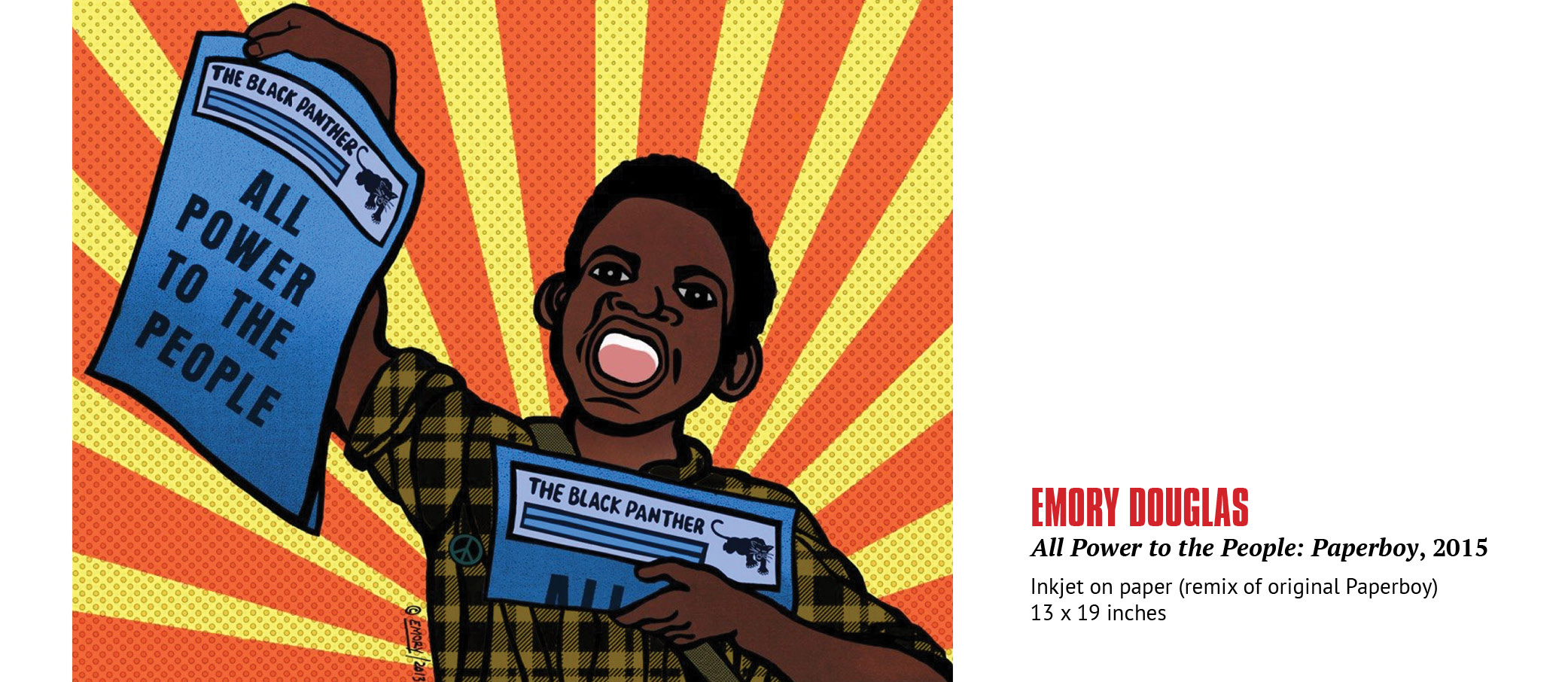

EMORY DOUGLAS

Bio

Emory Douglas has lived in the San Francisco Bay Area since 1951. After studying commercial art at City College of San Francisco, he was the Black Panther Party’s Revolutionary Artist and then Minister of Culture from February 1967 until the early 1980s. He art directed, designed, and illustrated for The Black Panther newspaper. Working with other artists and designers, his direction sustained the paper’s bold graphic look. After the BP newspaper ceased publication, he worked at the San Francisco Sun Reporter, a Black newspaper in San Francisco. In 2007, a monograph of Douglas’s work for The Black Panther brought his visual activism to new generations. Douglas had solo exhibitions at the Los Angeles Museum of Contemporary Art (2008) and the New Museum in New York (2009). In 2015, he became the first living Black person to win an AIGA Medal for contributing to the field of visual communications. In 2022, he was inducted into the Society of Illustrators’ Hall of Fame. In addition to exhibitions and inclusion in museum collections around the world, he speaks to all ages of students and audiences at a range of venues. Remaining community-minded, he often collaborates on a local project when he gives a talk or exhibits his work.

Artist Statement

The Battle Cry

“Culture Is A Weapon”

The battle cry "Culture Is A Weapon” is a powerful tool in all of its expressions and forms. It has the power to transform the Colonization Of The Imagination.

It is a reflection of our history of resistance and a product of that history.

Like the flower is a product of the seed.

“Culture Is A Weapon” at this time in history is the manifestation of the extreme reactionary times in the world we are living in today.

As a definition, it is not absolute but a continuation of expressions and interpretations, compassion, love, beauty, pain, and suffering that one feels and observes that penetrate the souls of the resistance via the resistors (We The People) against all forms of cruel and unjust authority.

“Culture Is A Weapon”—as a concept, it is the creative vehicle to communicate genuine truths about social concerns, truths you will never hear expressed by any reactionary or bureaucrat.

It is our duty as the makers of The Arts Of Resistance to always recognize the oppression of others.

The goal should be to make the message clear so that even a child can understand it.

Don’t be fooled by deception,

Know the rules before you break them.

Don’t lose sight of what the goal is.

ALL POWER TO THE PEOPLE!

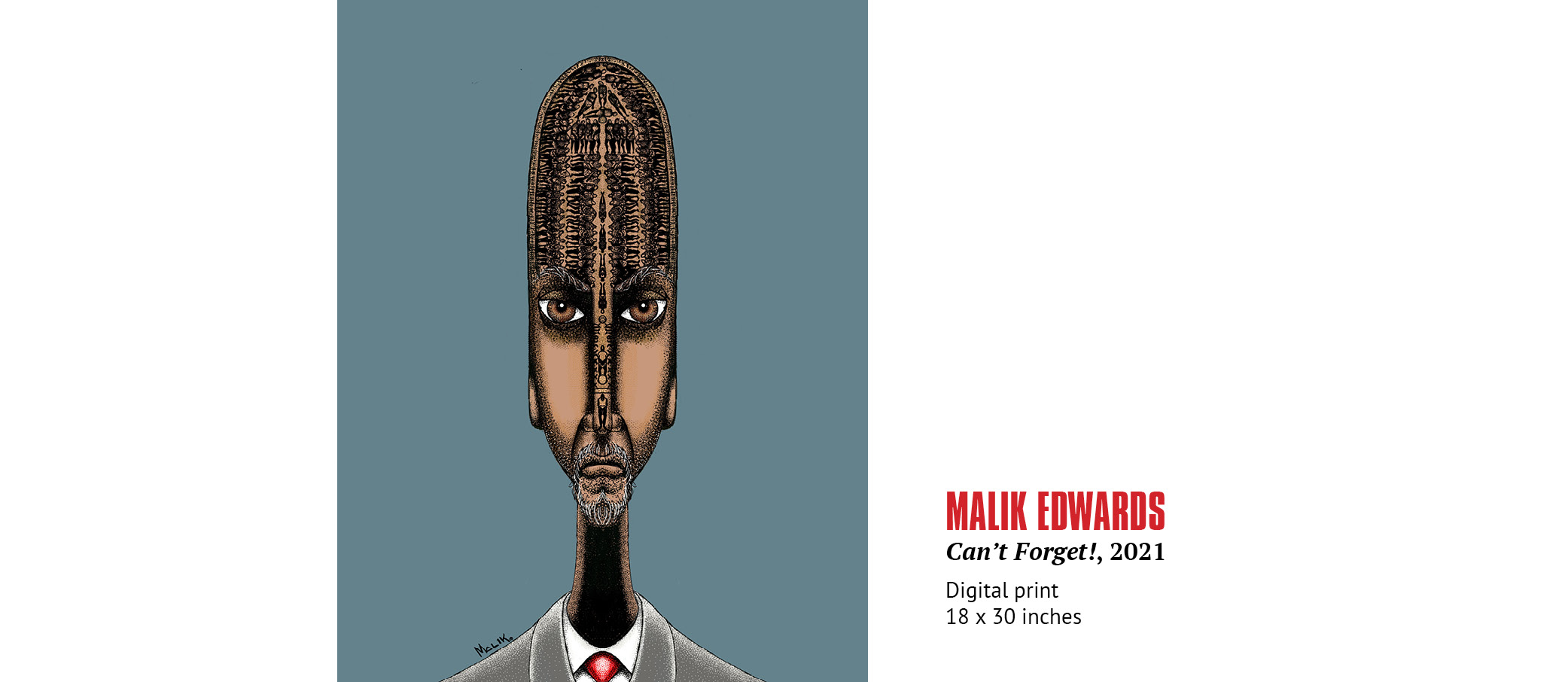

MALIK EDWARDS

Bio

When he was young, Malik Edwards discovered his talent by drawing Captain

Marvel, Superman, and other superheroes as Black, imagining himself in those roles. He joined the U.S. Marine Corps (USMC) in 1963 and served in Vietnam. After returning in 1966, the Corps recognized his artistic talents and assigned him to work as a Corps illustrator. In 1970, Edwards moved to Northern California and trained as an apprentice with the Black Panther Party’s (BPP) Minister of Culture, Emory Douglas. He learned the technical details of drawing, printing, and layout there, working alongside Gayle Asali Dickson. As the head of the Black Panther Party’s Washington, D.C. regional branch, he designed posters, flyers, and magazines for pro-Black events and anti-drug campaigns. Edwards left the BPP in 1973. He also taught art and worked as a drug counselor. Throughout his long career, Malik Edwards has used various media and methods as a graphic designer and artist. He later learned to use digital media and, most recently, incorporated AI (Artificial Intelligence) tools. His work has been exhibited in galleries in the Washington D.C. and San Francisco Bay areas. He currently works at a high school in Oakland, California, as a Restorative Practice Case Manager.

Artist Statement

I started working in black and white, then used color media, and now I create

digital color art using software applications. Recently, I have been playing with Artificial Intelligence (AI) prompts to create images of Black people who are underrepresented in AI. I accidentally discovered digital art with a phone drawing app, then switched to a tablet. The titles explain most of my work, and these elements are usually present—flowers, plants, wings, and sometimes animals. Flowers and plants represent the opening of the Divine Mind, wings represent the second Divine Thought, and elongated necks represent an upward seeking of the third Divine Consciousness. “Divine” does not refer to religion but to humans at our highest ideal. I am interested in the innate wisdom of mind, thought, and consciousness described by philosopher and author Sydney Banks. The writing of Thich Nhat Hahn, the Buddhist monk from Vietnam, continues to have great influence. Malcolm X is still the beginning of real learning for me. My first among many Western influences were Charles White and Elizabeth Catlett, René Magritte, and my teacher, Emory Douglas, of the Black Panther Party. I place myself among the Surrealist camp of artists. African sculpture and art also inspire my work. As an artist, I am giving a perspective that may help in the great truth dialogue.

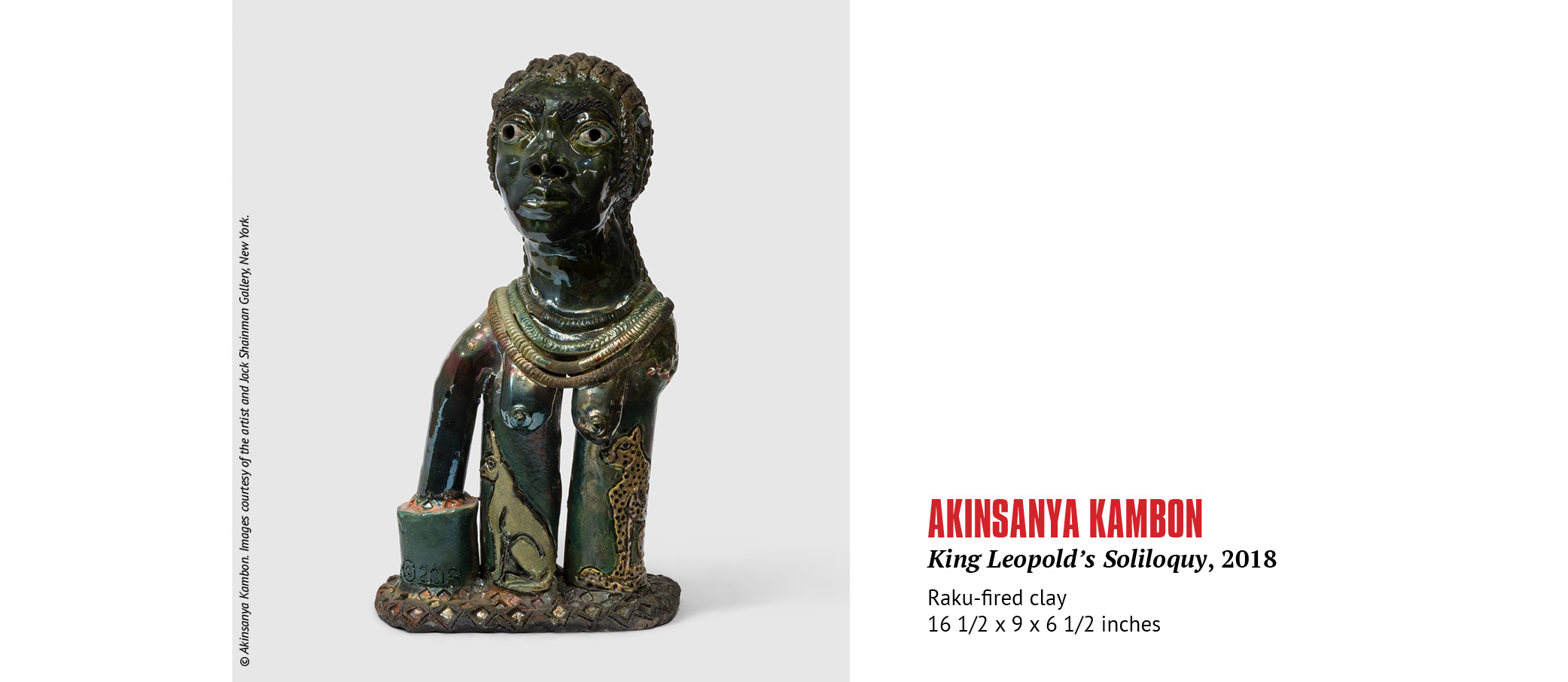

AKINSANYA KAMBON

Bio

Working in clay for almost four decades, Akinsanya Kambon creates vessels, figures, and wall plaques. These ceramics visualize narratives of the Black diaspora, including African histories, mythologies, and stories of violence and revolution from throughout Africa and the Americas. From 1966 to 1968, Kambon served in Vietnam with the U.S. Marine Corps as a combat illustrator and infantryman and was awarded several Purple Hearts for his bravery. Upon his return, he joined the Sacramento chapter of the Black Panther Party. As Lieutenant of Culture, he worked on the layout and illustrations for The Black Panther newspaper. Kambon earned a BA and an MA from California State University, Fresno. He has been working as a professor of art at the California State University, Long Beach, for twenty-six years and running free youth art programs devoted to African, Indigenous, and Latino culture out of his Long Beach studio. Recent solo exhibitions include the Jack Shainman Gallery, New York, and Crocker Art Museum, Sacramento. Recent group exhibitions were at the Hammer Museum, Los Angeles; Oakland Museum of California; and Joyce Gordon Gallery, Oakland. In 2023, Kambon received the Mohn Award for Artistic Excellence from the Hammer Museum of Contemporary Art.

Artist Statement

I was born into a legacy of revolution and rebellion, a calling to fight for change that is central to my work. Much of my art speaks to the struggles of oppressed people fighting for liberation. My lineage itself bears this history—my great-great-grandfather was among those who fought in the 1811 German Coast Rebellion, a powerful uprising of enslaved people in Louisiana. He was executed alongside one of his sons, and this legacy lives within me, driving my commitment to resist injustice. My art is an expression of that resistance.

For any artist or creative from an oppressed background, I believe that our work must confront the systems that perpetuate inequality, for these systems continue the same injustices our ancestors endured. To remain silent or complicit is to betray those who came before us. Our purpose is to make the world better for those who come after us, honoring the sacrifices made by generations before.

My earliest recognition came with drafting the Black Panther Coloring Book (1968), which was, in reality, a history book—not something meant to be colored in by kids. It told the story of African people kidnapped from their homeland and forced into slavery to build the economic foundations of this nation. Our labor powered this country’s rise to global dominance, and that history should not be forgotten. Through my work, I aim to ensure that this truth remains visible, refusing to let our contributions—and our struggles—be erased.

Colette Gaiter, curator

Bio

Colette Gaiter’s career started in graphic design and then morphed into digital and interdisciplinary art. Her visual work, which has been exhibited internationally, includes artist books, photographic digital prints, multimedia collage, assemblage, artist websites (from the early days of digital art), and interactive computer-based installations.

Now, she primarily writes about Black artists, designers, and visual culture in general. Since 2005, her essays and articles on the activist and former artist for the Black Panther Party, Emory Douglas, have appeared in a range of publications, including Black Panther: The Revolutionary Art of Emory Douglas and The Black Experience in Design. Other arts writing includes catalog essays for the Delaware Art Museum, the Poster House Museum in New York, and the Norman Rockwell Museum’s exhibition Imprinted: Illustrating Race. The Rockwell catalog essay was about Black Panther artists whose work is in Carrying On. She is currently working on a book about Emory Douglas’s continuing post-Black Panther Party work as an activist artist.

She retired as Professor Emerita in the Departments of Africana Studies and Art & Design at the University of Delaware. Her work as an educator and other creative pursuits have always included creative activism.

SUPPORT

Carrying On is made possible with support from our funders:

The Terra Foundation for American Art, established in 1978 and having offices in Chicago and Paris, supports organizations and individuals locally and globally with the aim of fostering intercultural dialogues and encouraging transformative practices that expand narratives of American art, through the foundation's grant program, collection, and initiatives.

The Terra Foundation for American Art, established in 1978 and having offices in Chicago and Paris, supports organizations and individuals locally and globally with the aim of fostering intercultural dialogues and encouraging transformative practices that expand narratives of American art, through the foundation's grant program, collection, and initiatives.