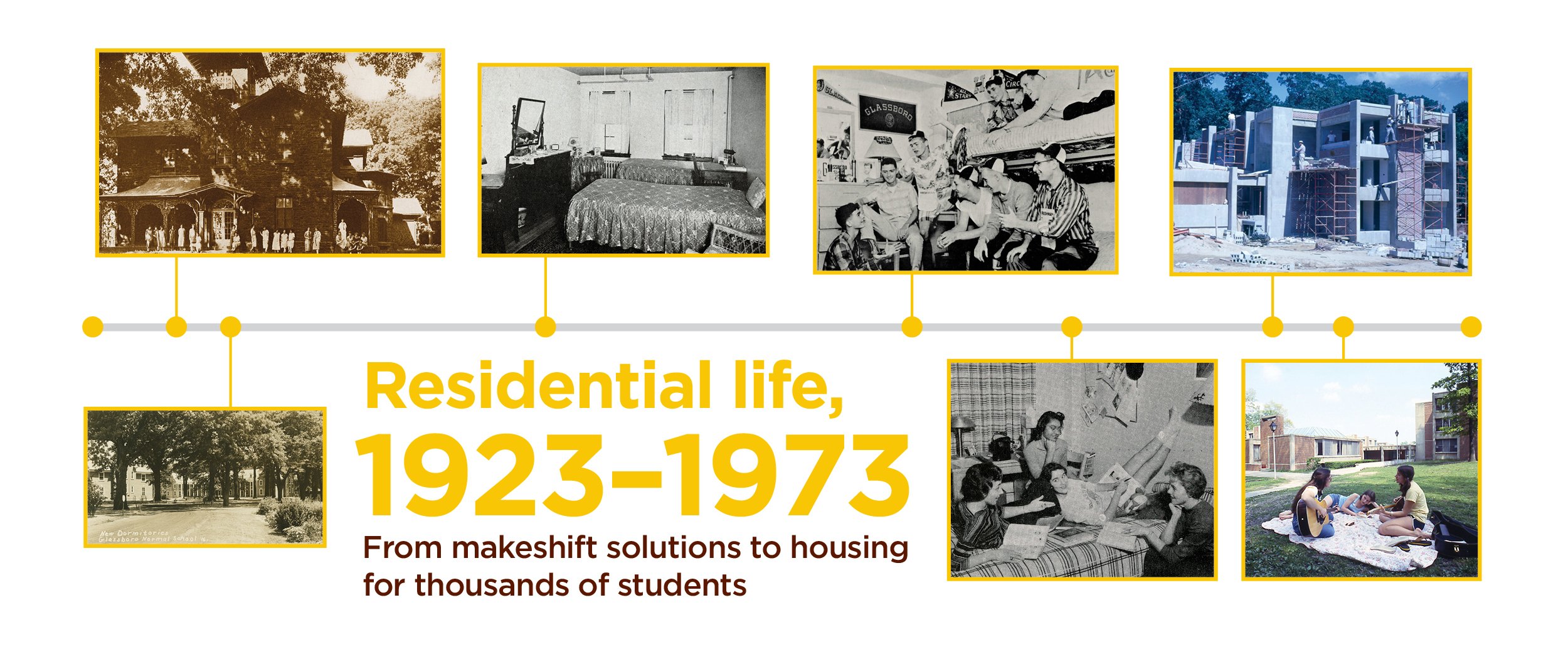

The early lack of student housing was among the New Jersey State Normal School at Glassboro’s biggest challenges, as Dr. Robert Bole, Glassboro State College administrator and historian, chronicled in his book “More Than Cold Stone.”

The days before dorms

The first students to live on campus at Glassboro Normal School were housed in mansions—but it wasn’t as luxurious as it sounds.

The Warrick Mansion on the corner of High Street and Academy Street became the first approximation of residence halls, housing 22 female students during the school’s first year. Students slept on donated camp-style cots and shared a single bathroom, paying $7 per week for room and board.

The school arranged for dozens more students to stay in private homes at the Neiling House, the Satterfield House, the Ridge House and the Ackley Apartments. The Whitney Mansion (otherwise known as the Hollybush Mansion) also provided some of the school’s first campus housing. In these private homes, as many as 10 students could share a bathroom or even a single closet.

The school needed to build on-campus dormitories. That would require more state funding.

Life in the early dorms at Glassboro Normal School

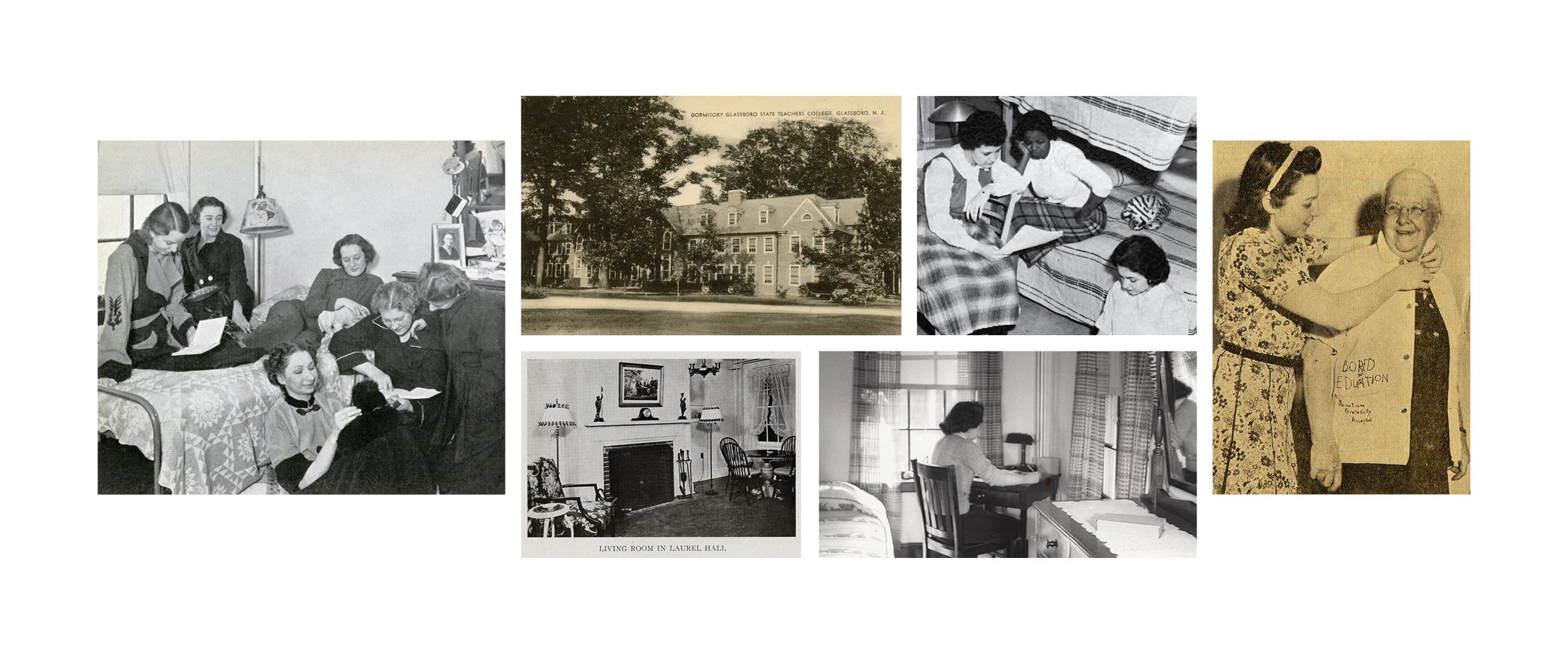

The school’s first true dormitory, Laurel Hall, opened in 1928 and housed 80 students. Just in time for the 1930-1931 academic year, Oak Hall opened to house 80 students.

For students who populated the new dormitories, life in on-campus housing was vibrant, if strict.

Students faced a dorm-wide 6:45 a.m. weekday wake-up time, a mandatory two-hour study period and a 10:15 p.m. bedtime. “Dormies” had to keep their rooms neat and ready for inspection by the principal at all times.

Despite the rules, students had plenty of fun in the dorms, dancing and playing ping-pong and shuffleboard in the community rooms. During the spring semester of 1936, students put on an amateur hour and arranged an auction of unclaimed clothing.

More important than the buildings or activities in making life in the dorms memorable were the people—like Grandma Smith, for example.

During the 1936-1937 school year, young women recently out of high school shared the Oak Hall dorm with Mrs. Sarah Smith, a retired teacher who, according to Bole, was (at least, as of 1973) “the oldest student who has ever attended Glassboro.”

Far from cramping her much-younger dormies’ style, Smith became a beloved part of the community.

“To many Mrs. Smith symbolized the Glassboro student of the Depression era, proud, cheerful and courageous,” Bole wrote.

Integration in campus housing

The first dorm-dwellers at Glassboro Normal School were strictly white women, as was most of the student body.

As men began to make up more of the student population during the 1930s, the need for housing for male students grew. The first 23 men to ever live on campus moved into Oak Hall in 1939.

“Rather than becoming perturbed, the girls were pleased” with the inclusion of men in their midst, Bole wrote.

Oak Hall was also the first desegregated dormitory on Glassboro’s campus. By the late 1940s, white and black female students were living side by side in multiple units of Oak Hall, making the school “among the first to practice as well as preach the brotherhood of man principle,” Bole wrote.

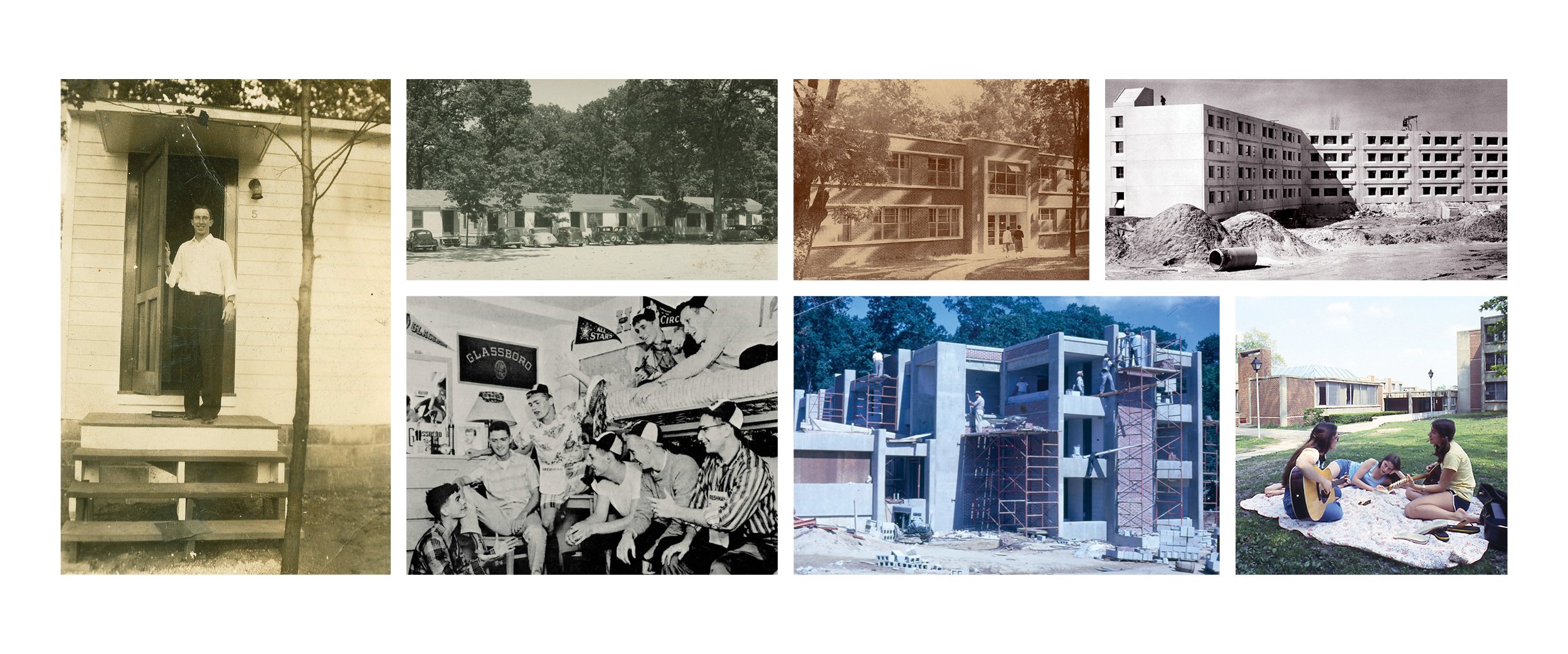

Glassboro Normal School outgrows its available housing

The end of World War II brought an influx of veterans and the need for even more student housing. To accommodate this need, 17 temporary housing units known as the “Shacks” were established on campus.

As plans for new construction inched forward, the shortage of student housing only worsened. “By 1957 getting a dormitory room became as difficult as obtaining tickets to an Army-Navy football game,” Bole remembered.

Bunk beds allowed 60 double rooms in the dorms to squeeze in a third occupant, while another 60 students became the first to live in approved townhomes.

In 1961, the construction team broke ground on long-delayed dorm projects. Soaring enrollment at what had then become Glassboro State College had changed the original plans for the women’s dormitory, Linden Hall, from 100 beds to 200 beds and the men’s dormitory, Mullica Hall, from 50 beds to 100 beds.

Both dorms opened to students at the start of the 1962-1963 school year—and it’s a good thing they did.

Enrollment more than doubled between 1960 and 1965. Even the two new residence halls weren’t enough to ease the growing pains.

As the 1965-1966 academic year approached, the dormitories designed to house 585 students now had to accommodate 757 students. Nearly 900 students were looking for off-campus housing.

This housing struggle led to the first off-campus apartment housing for seniors. By 1967, 221 seniors were living in off-campus apartments.

The 500-bed freshman women’s dormitory Mimosa Hall was still under construction when it opened in September 1967. Student volunteers rushed to clean and make the new dorms livable.

The off-campus Mansions Apartments became part of the school’s property in late 1970, housing 300 students. Next came the Triad, located at the intersection of Route 322 and Joseph Bowe Boulevard, which housed 282 students in 1972.

In 1973, Edgewood Park Apartments was built to accomodate students in 95 two-bedroom apartments across four buildings.

More freedom in dorm life

Like the dormitories themselves, the rules and freedoms students encountered in their residence halls changed with the times.

Although dorm curfews were still in effect as the 1960s closed, student efforts— through activism, negotiations and, at times, ultimatums—brought about more liberal curfews and dorm visitation policies. The longstanding curfew policy for women living in the dorms ended in the early 1970s.

Rowan’s story has always been one of growth. The growth of the institution’s dorms encompasses the buildings themselves, the integration of students of different sexes and races and the rights of students living on campus.