From its early days, Rowan University has been a “College that Cares,” as Dr. Robert Bole, Glassboro State College administrator and historian, wrote in his book “More Than Cold Stone.” Over the first century of the institution’s existence, its students have cared deeply about everything from anti-war movements to furthering their own rights and freedoms on campus.

Student rights in the 1920s and 1930s

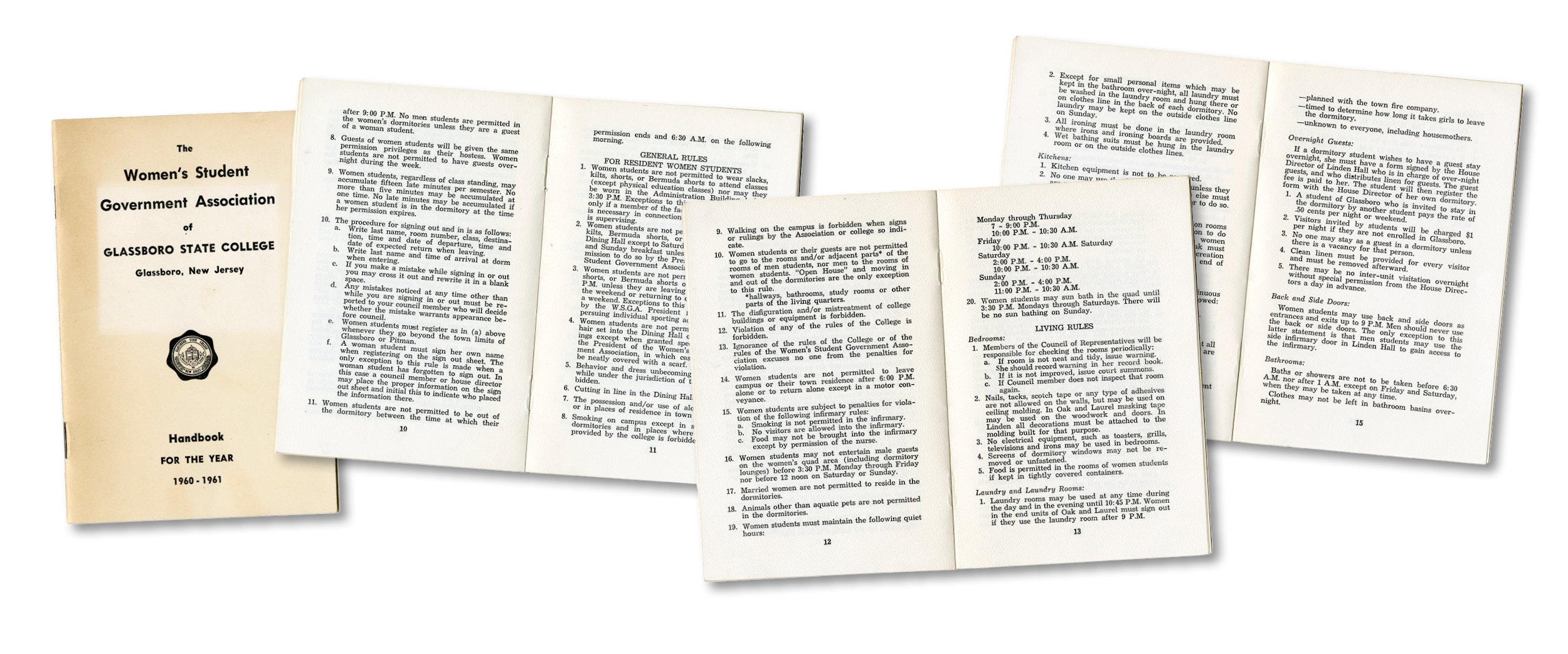

The first female students to grace the New Jersey State Normal School at Glassboro weren’t allowed to wear lipstick or cut their hair into the popular bobbed style of the day. Strict dorm curfews persisted (though relaxed) until the early 1970s. Female students needed parental permission to bring male guests to school dances.

Under the administration of Dr. Edgar F. Bunce, who took office as president of Glassboro State Teachers College in 1937, some school and dorm rules were “liberalized,” Bole wrote. Thanks to what Bole called the “Bunce New Freedom student movement,” students no longer felt like they were still in high school.

A history of welcoming student participation

Beginning in the late 1930s, students were encouraged to get involved in solving college problems. Bunce facilitated increased student participation in college policy formation on all sorts of topics.

“I challenge the faculty and students to make constructive and confidential suggestions to me in writing,” Bole quoted Bunce as saying. Students responded with suggestions “too numerous to begin publishing.”

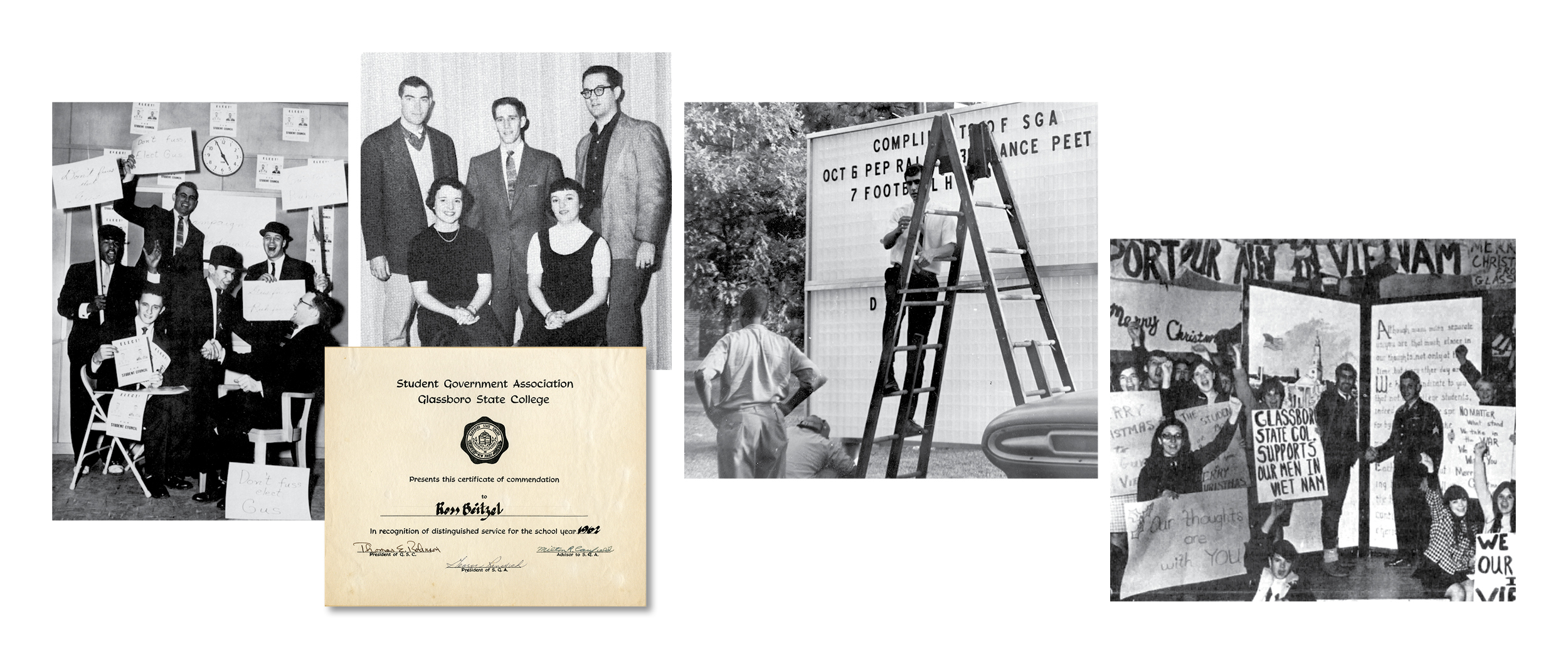

The next president, Dr. Thomas E. Robinson, would only expand students’ involvement. During the 1958-1959 school year, students first had the opportunity to join some of the committees Robinson established. By the 1962-1963 school year, more than half of these committees included student representatives. The Robinson administration also saw the founding of the Council on Student Life (later called the Student Government Association) and the Student-Faculty Cooperative Association.

Keeping the lines of communication open

The open communication and designated channels for student involvement that Bunce first established would characterize student rights movements at Glassboro for decades to come.

Throughout the 1961-1962 school year, President Robinson and student leaders held monthly face-to-face meetings that helped realize changes in everything from exam procedures to parking regulations. Still, when the administration put into place policy changes that students felt were unilateral and unfair, these lines of communication nearly broke down.

There were occasional acts of insubordination—like the secret formation of an illicit social fraternity in 1962 and a 1969 ultimatum to allow open dormitory visitation or face the threat of “hordes of male students” barging into a women’s dormitory after curfew. Still, Glassboro State College students earned expanded rights not through riotous protests or even peaceful civil disobedience. Rather, most gains in students’ rights were achieved primarily through what Bole called “the law-and-order approach of sitting down to reason together.”

Peace, not violence

In the mid- to late-1960s, when college campuses became the scenes of chaotic and sometimes violent confrontations, Glassboro students didn’t seize, pillage or burn campus buildings or property. The students weren’t apathetic; they just found more peaceful and productive ways to demonstrate their care and compassion.

Students visited wounded veterans and sent thousands of Christmas cards to soldiers serving in the Vietnam War. Dozens of students held a daylong vigil in honor of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. following the activist’s assassination. More than 500 Glassboro students joined a multi-school peaceful march in Trenton in support of increased funding for higher education in New Jersey.

As the 1960s drew to a close, students pursued more liberal curfews, the freedom to live off-campus at an earlier age and more involvement in college policymaking in general. By and large, they still went through the long-established channels of communication with college administrators. In doing so, students achieved many of their goals during the 1969-1970 school year.

It helped that the administration was sympathetic to students’ concerns, both on campus and in the world at large. In his 1970 President’s Inaugural Program, Dr. Mark M. Chamberlain expressed an intention to, as Bole wrote, “tactfully and wisely encourage and wisely channel student activism.”

Chamberlain wanted to shift what he called the “strongly authoritarian atmosphere” at Glassboro State College, so it’s little surprise that he encouraged students to become more involved in making changes. Far from discouraging students’ protests, Chamberlain served as a speaker at Glassboro State College’s 24-hour Vietnam Moratorium observance in October 1969. Chamberlain concluded his speech with a peace sign and the words, “Let us opt for life and not destruction. Peace!”

From the beginning, Glassboro students found their own ways—peaceful and altruistic ways—to make changes on campus and to make the world a better place. This unique approach to civic movements and student rights at Glassboro spared the community the heartaches that became all too familiar at colleges across the country during the 1960s and set the tone for the collaborative relationship students, faculty and administration at Rowan University share today.