Image Alternative Text: Depicted is the World Health Organization (WHO) 75th anniversary image. The image reads, "75" and "Health for All." Beneath these words is an image of a person in a bright-colored blue, orange, green, and purple patterned outfit with images of health and medical symbols. The image is via the WHO.

Written by:

Patricia Fortunato, Content and Program Manager, Clinical Research and Grants, NeuroMusculoskeletal Institute (NMI); and Mental Health and Suicide Prevention Training and Content Developer, Department of Psychiatry, Rowan–Virtua School of Osteopathic Medicine (Rowan–Virtua SOM) (fortun83@rowan.edu)

Thank you to staff and faculty colleagues across Rowan University, for collaborating and helping to provide input and resources for Disability Employment Awareness Month at go.rowan.edu/ndeam.

Together with all Rowan colleges and schools, we are committed to supporting neurodivergent people and people with disabilities; and overall diversity, equity, and inclusion across our campuses and communities.

Interested in contributing to the Rowan University DEI website/blog and/or social media? Please complete the following brief interest form and share with student groups and colleagues across all Rowan colleges and schools: go.rowan.edu/deicontent

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), health equity is attainable when all people can attain "their full potential for health and well-being."1 Health, and health equity, are correlated with conditions in which people are born, live, and work, in addition to biological determinants. Structural determinants (economic, political, legal) and social norms influence distribution of power further determined by conditions in which people are born, live, and work.2 Living conditions can be and are frequently worsened by discrimination based on sex, gender, race, ethnicity, disability, age, and/or other factors.1 Understanding health equity requires identifying and eliminating inequities.

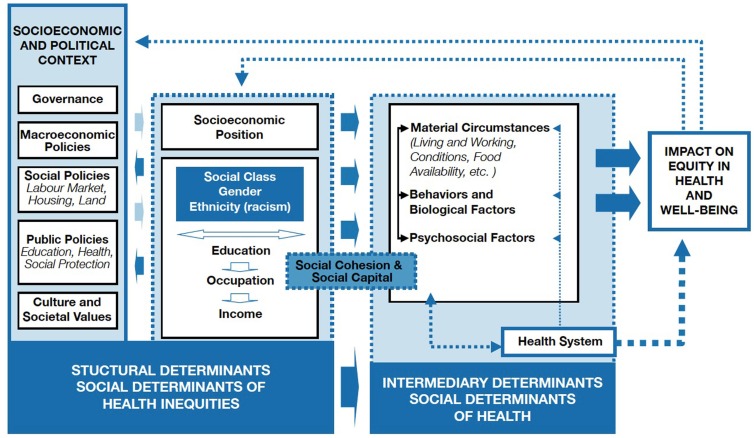

Image Alternative Text: Depicted is the World Health Organization (WHO) conceptual framework for action on the social determinants of health (SDOH). The figure is divided as structural and intermediary determinants, with structural determinants comprising societal, economic, and political context of a person's life, linking to their socioeconomic position.

A person's socioeconomic position determines intermediary determinants, including biological and/or behavioral factors, psychosocial circumstances, and the health care system, and likelihood of health conditions caused by poor living conditions. These living conditions can be linked to structural determinants if a person experiences loss of income, among other factors, reducing socioeconomic status.

The image is via the WHO.1

The term intersectionality was conceived in 1989 by Kimberlé Crenshaw,3 civil rights advocate and scholar of critical race theory; Black feminist theory; and race, racism, and the law. Intersectionality refers to the double bind of racial and gender prejudice that Black women experience.4–5 The term has since expanded to include identity aspects related to race and disability. The socio-historical relationship between race, gender, and disability in the United States perpetuates inequalities and disparate treatment that harm Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC).6 Racially and ethnically minoritized people with disabilities continue to experience the prevalence of racism and discrimination, and thus increased disparities in access to longitudinal integrated, trauma-informed, and culturally responsive care; health and health care outcomes; and access to SDOH including employment.7–10

Of the 26% of adults living in the U.S. who experience disabilities, increased disabilities are prevalent among BIPOC.11 Data also indicates that BIPOC and people with disabilities experience disparities in access to and retainment of equitable and evidence-based care,12–14 reporting unmet health care needs at higher levels than white, non-Hispanic, and non-disabled people.15–16 Further barriers include BIPOC and people with disabilities experiencing underinsurement and un-insurement,17 experiences of undocumentation,18 and overall lack of culturally responsive care.19–20 BIPOC with disabilities can experience both racism and ableism; this racism and ableism further increases disparities in health outcomes.11 Further data indicates that people with intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDD) who identify as racial and ethnic minorities experience worse health outcomes compared to white patients with IDD;22–23 and disparities in health care access and utilization for women with IDD who identify as racial and ethnic minorities.24 Among BIPOC autistic children and those with autism spectrum disorder (ASD), disparities in diagnosis and care have resulted in delayed identification and misdiagnoses.25–27

People with substance use disorder (SUD) are designated protections from discrimination under the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA).28 The ADA prohibits discrimination against people with SUD who are in recovery and who are not engaging in illicit substance use.28–29 The law does not prohibit employers from maintaining substance-free workplace policies, and it does not ensure protection to people who are currently using illicit substances. Per the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), an agency within the United States Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), the ADA specifically makes it illegal for employers to discriminate against people with SUD who have already secured treatment for addiction and who are in recovery.30 Additional information is available on the SAMHSA website.

Still, across the U.S., persistent disparities in access to and retainment of evidence-based care for BIPOC with SUD stigmatize and marginalize lives and can result in disproportionate negative effects on communities and lack of access to SDOH.31–38 Solutions must be identified to reduce racial disparities in access to SUD treatment. Centering the experiences of BIPOC with SUD in the statewide and national discourse, and listening to and elevating BIPOC with SUD, is critical to increasing engagement and access.

*Educational information and supportive resources focused on stigma, substance dependence and SUD/addictions treatment, and related terms and issues are available at go.rowan.edu/recovery.

References

- Commission on Social Determinants of Health. (2008). Closing the Gap in a Generation: Health Equity through Action on the Social Determinants of Health: Final Report of the Commission on Social Determinants of Health. World Health Organization.

- World Health Organization. (2021). It's Time to Build a Fairer, Healthier World for Everyone, Everywhere. Health Equity and its Determinants.

- Crenshaw, K. (2013). Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics. In Feminist Legal Theories (pp. 23-51). Routledge.

- Shannon, G., Morgan, R., Zeinali, Z., Brady, L., Couto, M. T., Devakumar, D., ... & Muraya, K. (2022). Intersectional Insights into Racism and Health: Not Just a Question of Identity. The Lancet, 400(10368), 2125-2136.

- King-Mullins, E., Maccou, E., & Miller, P. (2023). Intersectionality: Understanding the Interdependent Systems of Discrimination and Disadvantage. Clinics in Colon and Rectal Surgery.

- Harris, J. E. (2021). Reckoning with Race and Disability. Yale Law Journal Forum+ H2332.

- Armenti, K., Sweeney, M. H., Lingwall, C., & Yang, L. (2023). Work: A Social Determinant of Health Worth Capturing. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(2), 1199.

- Friedman, C. (2023). Ableism, Racism, and the Quality of Life of Black, Indigenous, People of Colour with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 36(3), 604-614.

- Green, J., Millner, U. C., Ellis, J., Kelleher, A., & Satgunam, S. A. (2023). Impact of the COVID–19 Pandemic on the Career Development of Individuals with Psychiatric Disabilities. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 46(2), 163.

- National Disability Institute. (2021). Race, Ethnicity, and Disability: The Financial Impact of Systemic Inequality and Intersectionality.

- Varadaraj, V., Deal, J. A., Campanile, J., Reed, N. S., & Swenor, B. K. (2021). National Prevalence of Disability and Disability Types Among Adults in the US, 2019. JAMA Network Open, 4(10), e2130358-e2130358.

- Caraballo, C., Ndumele, C. D., Roy, B., Lu, Y., Riley, C., Herrin, J., & Krumholz, H. M. (2022). Trends in Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Barriers to Timely Medical Care Among Adults in the US, 1999 to 2018. In JAMA Health Forum (Vol. 3, No. 10, pp. e223856-e223856). American Medical Association.

- Smith, M. A., Hendricks, K. A., Bednarz, L. M., Gigot, M., Harburn, A., Curtis, K. J., ... & Farrar-Edwards, D. (2021). Identifying Substantial Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Outcomes and Care in Wisconsin Using Electronic Health Record Data. WMJ: Official Publication of the State Medical Society of Wisconsin, 120(Suppl 1), S13.

- Fiscella, K., & Sanders, M. R. (2016). Racial and Ethnic Disparities in the Quality of Health Care. Annual Review of Public Health, 37, 375-394.

- Manuel, J. I. (2018). Racial/Ethnic and Gender Disparities in Health Care Use and Access. Health Services Research, 53(3), 1407-1429.

- Stransky, M. L., Jensen, K. M., & Morris, M. A. (2018). Adults with Communication Disabilities Experience Poorer Health and Healthcare Outcomes Compared to Persons without Communication Disabilities. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 33, 2147-2155.

- Mahmoudi, E., & Meade, M. A. (2015). Disparities in Access to Health Care Among Adults with Physical Disabilities: Analysis of a Representative National Sample for a Ten-Year Period. Disability and Health Journal, 8(2), 182-190.

- Echave, P., & Gonzalez, D. (2022). Being an Immigrant with Disabilities. Urban Institute.

- Eken, H. N., Dee, E. C., Powers, A. R., & Jordan, A. (2021). Racial and Ethnic Differences in Perception of Provider Cultural Competence Among Patients with Depression and Anxiety Symptoms: A Retrospective, Population-Based, Cross-Sectional Analysis. The Lancet Psychiatry, 8(11), 957-968.

- Ferdinand, A., Massey, L., Cullen, J., Temple, J., Meiselbach, K., Paradies, Y., ... & Kelaher, M. (2021). Culturally Competent Communication in Indigenous Disability Assessment: A Qualitative Study. International Journal for Equity in Health, 20(1), 1-12.

- Blaskowitz, M. G., Scott, P. W., Randall, L., Zelenko, M., Green, B. M., McGrady, E., ... & Lonergan, M. (2020). Closing the Gap: Identifying Self-Reported Quality of Life Differences Between Youth With and Without Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities. Inclusion, 8(3), 241-254.

- Lin, L. Y., & Huang, P. C. (2019). Quality of Life and its Related Factors for Adults with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Disability and Rehabilitation, 41(8), 896-903.

- Horner-Johnson, W., Akobirshoev, I., Amutah-Onukagha, N. N., Slaughter-Acey, J. C., & Mitra, M. (2021). Preconception Health Risks among US Women: Disparities at the Intersection of Disability and Race or Ethnicity. Women's Health Issues, 31(1), 65-74.

- Constantino, J. N., Abbacchi, A. M., Saulnier, C., Klaiman, C., Mandell, D. S., Zhang, Y., ... & Geschwind, D. H. (2020). Timing of the Diagnosis of Autism in African American Children. Pediatrics, 146(3).

- Aylward, B. S., Gal-Szabo, D. E., & Taraman, S. (2021). Racial, Ethnic, and Sociodemographic Disparities in Diagnosis of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 42(8), 682.

- McNally Keehn, R., Ciccarelli, M., Szczepaniak, D., Tomlin, A., Lock, T., & Swigonski, N. (2020). A Statewide Tiered System for Screening and Diagnosis of Autism Spectrum Disorder. Pediatrics, 146(2).

- Wiggins, L. D., Durkin, M., Esler, A., Lee, L. C., Zahorodny, W., Rice, C., ... & Baio, J. (2020). Disparities in Documented Diagnoses of Autism Spectrum Disorder Based on Demographic, Individual, and Service Factors. Autism Research, 13(3), 464-473.

- United States Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. Titles I and V of the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 (ADA).

- United States Department of Justice. (2009). Americans With Disabilities Act of 1990, As Amended.

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Federal Laws and Regulations.

- Holland, W. C., Li, F., Nath, B., Jeffery, M. M., Stevens, M., Melnick, E. R., ... & Soares III, W. E. (2023). Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Emergency Department-Initiated Buprenorphine Across Five Health Care Systems. Academic Emergency Medicine.

- Lindsay, A. R., Winkelman, T. N., Bart, G., Rhodes, M. T., & Shearer, R. D. (2023). Hospital Addiction Medicine Consultation Service Orders and Outcomes by Patient Race and Ethnicity in an Urban, Safety-Net Hospital. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 1-8.

- Lee, H., & Singh, G. K. (2023). Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Monthly Trends in Alcohol-Induced Mortality Among US Adults from January 2018 through December 2021. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 1-8.

- Barnett, M. L., Meara, E., Lewinson, T., Hardy, B., Chyn, D., Onsando, M., ... & Morden, N. E. (2023). Racial Inequality in Receipt of Medications for Opioid Use Disorder. New England Journal of Medicine, 388(19), 1779-1789.

- Dong, H., Stringfellow, E. J., Russell, W. A., & Jalali, M. S. (2023). Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Buprenorphine Treatment Duration in the US. JAMA Psychiatry, 80(1), 93-95.

- Winograd, R., Budesa, Z., Banks, D., Carpenter, R., Wood, C. A., Duello, A., ... & Smith, C. (2023). Outcomes of State Targeted/Opioid Response Grants and the Medication First Approach: Evidence of Racial Inequities in Improved Treatment Access and Retention. Substance Abuse, 08897077231186213.

- Austin, A. E., Durrance, C. P., Ahrens, K. A., Chen, Q., Hammerslag, L., McDuffie, M. J., ... & Jarlenski, M. (2023). Duration of Medication for Opioid Use Disorder During Pregnancy and Postpartum by Race/Ethnicity: Results from 6 State Medicaid Programs. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 247, 109868.

- Miles, J., Treitler, P., Lloyd, J., Samples, H., Mahone, A., Hermida, R., ... & Crystal, S. (2023). Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Buprenorphine Receipt among Medicare Beneficiaries, 2015–19: Study Examines Racial and Ethnic Disparities in the Receipt of Buprenorphine among Medicare Beneficiaries. Health Affairs, 42(10), 1431-1438.