Professor focuses on social justice in STEM

Dr. Elliott Karetny, Adjunct Professor in the Department of STEAM Education

In this image, I am standing before one of the five murals my students have painted to represent all facets of the natural world. This one represents the past, present, and future of the local ecosystem and is adorned with Walt Whitman quotations. He spent time in South Jersey enjoying the Timber Creek, which is the namesake of my high school.

Tell us about the DEI research that you are doing

My research explores the use of social justice (environmental, specifically) to motivate high school science students. I have found that including social and political elements in my lessons motivates students. Even more so, it empowers them to ask more questions (which is the foundation of an scientific inquiry) as well as to participate more both in and out of the classroom. Those elements generally include social justice concerns and engage the students when they see how high the stakes are when we look at the impact of environmental problems ranging from climate change to water pollution. Now more than ever, students become comfortable starting conversations and aspiring to action about conflicts they hear about elsewhere, including disaster relief, energy production and even the educational system itself. Teaching this way has made it seamless to integrate lessons on the origins and management of the pandemic in my environmental science class.

What made you want to undertake this work?

I decided to undertake this work when I noticed that fewer and fewer students were interested in classes that focused mainly on a science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) approach. I have always valued the role of scientists in making decisions about environmental and human health. We were overlooking the human side of science, which includes not only the arts, but also philosophy, politics, sociology, history, and much more. So, a justice-based approach interweaves civic engagement and artistic expression as a reason and means to do science.

Why would our students at Rowan University be interested in this work?

Students at Rowan University would be interested in my work because it opens doors to interdisciplinary learning. In my coronavirus seminar, we looked at not only the evolution and transmission of SARS-CoV-2, but also the emotional, economic, and social impacts of personal protective measures in different communities. We touched on everything from the long-standing mistrust of the science in the Black community to international research collaborations that may be overshadowed by geopolitical tensions. In my education course, my teacher candidates reflect deeply on their own biases to develop more equitable and inclusive teaching philosophies and pedagogies. They build confidence in bringing their own identities into their classrooms and meeting their students in a third space that thrives on collaboration and collectivism. They are able to design lessons with their students in mind more than ever, as am I.

Is there anything else you’d like to tell us about your work?

I find that this work helps engage and empower me as a member of the Rowan community. I participate on the Rowan Thrive. One of the most powerful aspect of this type of research is that it depends on the very people it proposes to benefit: the students themselves.

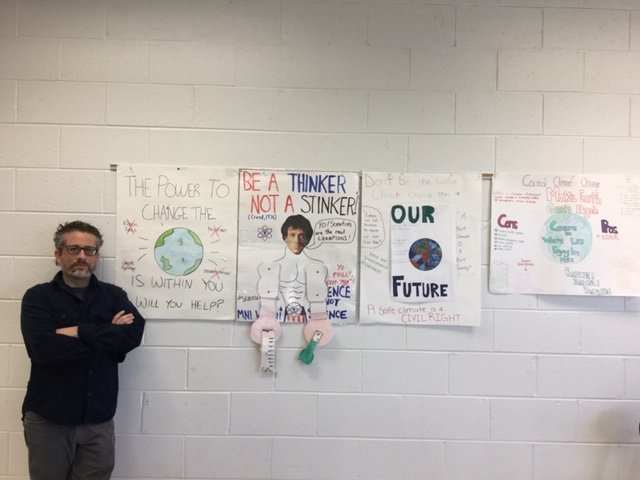

In this image, I am standing before protest signs that my students (and I) have made through the years to practice amplifying our voices for change.