In 1948, the mood at the New Jersey State Teachers College at Glassboro was ebullient. The school was 25 years old, the second World War was over and returning veterans were bringing the campus to life. "I was flying airplanes in the Phillipines during the war," recalls Harold Cook '48. "I was almost 21 years old when I went to Glassboro." The College had much to celebrate, having evolved from a two-year normal school to a four-year state college within its first 12 years. Yet, the institution was still in its infancy, graduating approximately 100 students that year compared to 1,800 today. When the school was founded in 1923 to train teachers for South Jersey elementary schools, it was headed by Jerohn J. Savitz, who "realized that teachers of elementary grades need character, culture, understanding of children and practical training in teaching in order to be successful." By 1935, the school included kindergarten-primary and general elementary programs and became the four-year New Jersey State Teachers College.

The war's end brought curriculum changes. Temporarily, a two-year junior college for veterans offered business administration and pre-engineering courses. After two years, instead of transferring, many of the men chose to stay at Glassboro. "That's when they brought in the junior high school majors because that's what young men were interested in—not elementary education," remembered Edith Huston, who served under four presidents and retired as executive assistant to the president.

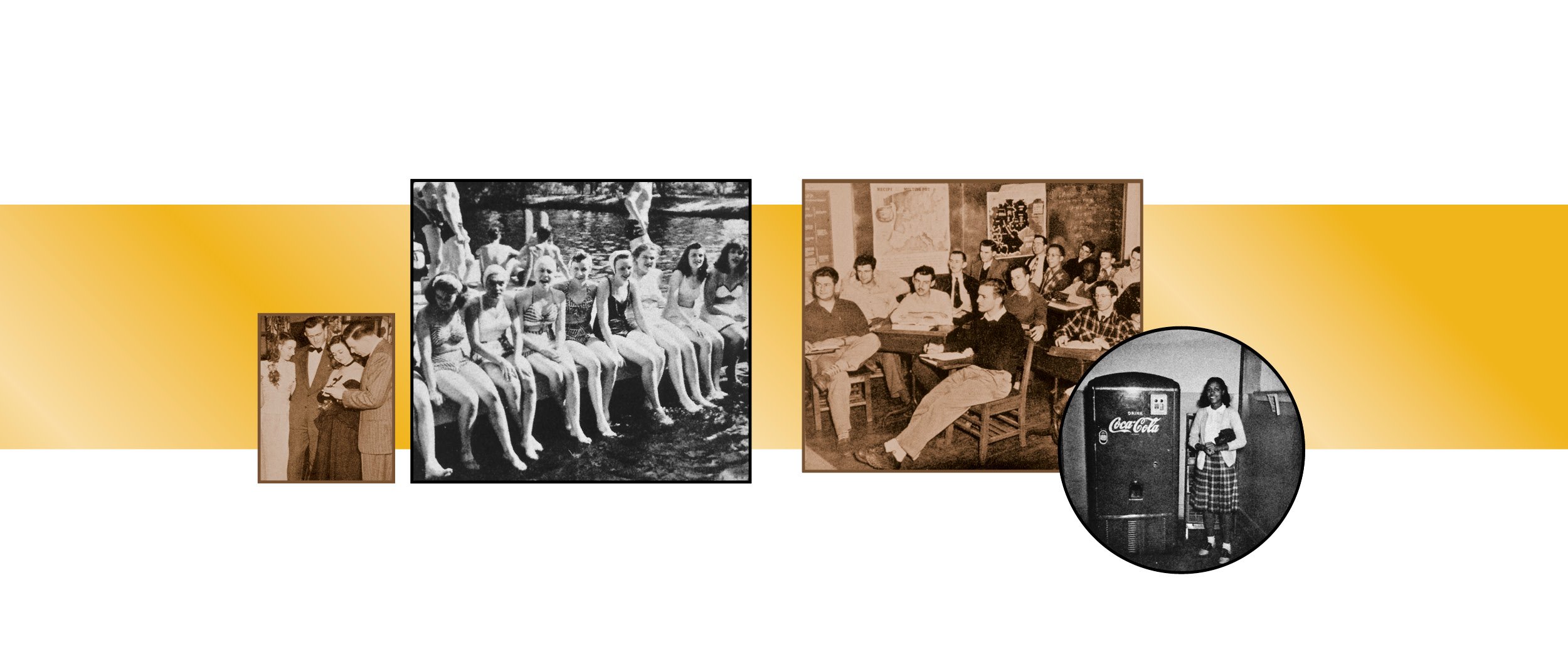

Students on campus welcomed the change. "The coming of the veterans has rejuvenated the school," reported the 1948 yearbook, The Oak. "Teachers College classes that were once composed solely of women are now interspersed with men. The discussions are enlivened by the varied and extensive backgrounds of these newcomers." The presence of men meant two things: more dances and sports. "We were able to have a football team because of all these returning veterans," said Huston. During the Glassboro Yellow Jackets' second season, the anniversary of the College was commemorated with a Homecoming football game, as well as alumni events, open house at the Whitney Mansion (now Hollybush) and a rededication service that closely followed the original 1923 school dedication ceremony.

At the time of the 25th anniversary, classes were held in Bunce Hall and temporary frame buildings were erected for the Junior College (where Memorial Hall now stands). "Only the administrative building was up at the time—Bunce Hall and two dorms, one for the girls and one for the boys," recalled Cook. "Now I'm flabbergasted at the size of the institution." The dorms—Oak and Laurel—were changing in another way. "The civil rights movement was just starting so the dorms were just beginning to integrate, remembered Evelyn Sellers '48.

At the time of the 25th anniversary, classes were held in Bunce Hall and temporary frame buildings were erected for the Junior College (where Memorial Hall now stands). "Only the administrative building was up at the time—Bunce Hall and two dorms, one for the girls and one for the boys," recalled Cook. "Now I'm flabbergasted at the size of the institution." The dorms—Oak and Laurel—were changing in another way. "The civil rights movement was just starting so the dorms were just beginning to integrate, remembered Evelyn Sellers '48.

Getting to campus was simpler then, too. "I commuted from Runnemede with a friend," said Cook. "We would make the run down Delsea Drive in about ten minutes. We only met with five or six cars.

Campus activities flourished after the war. Faculty and students were required to attend school concerts. Teas and receptions were given, and students participated in clubs and organizations. The Whit, then a monthly newspaper, had clinched first place three times at the Columbia Press Conference in New York City in its first ten years of publication.

The atmosphere on campus was homey during those years. "Everyone knew everyone," recalled Clarke Pfleeger, retired 41-year music professor and former Music Department chair. The small student population meant assemblies could be held in what is now known as Tohill Auditorium. "That was a time when everyone got to know each other," he said. The freshmen, sophomore, junior and senior classes competed to present the best programs.

Dinners also held a touch of home. "They were really good meals," said Lucille Pfleeger, wife of Clarke Pfleeger, who lived on campus with her husband during that period. Food was served family-style on tablecloths in the cafeteria in the basement of Bunce Hall, and included fresh asparagus, peaches and other produce grown on a farm operated by the College.

Clarke Pfleeger shared dinner supervision with two other faculty members who were charged with the duty of making sure students were properly attired. Men wore suit jackets, shirts and ties and women wore dresses. "No one was allowed to leave the table until everyone was finished," added Lucille Pfleeger.

Clarke Pfleeger shared dinner supervision with two other faculty members who were charged with the duty of making sure students were properly attired. Men wore suit jackets, shirts and ties and women wore dresses. "No one was allowed to leave the table until everyone was finished," added Lucille Pfleeger.

Through such measures of decorum the administration strove to shape the character of the ideal college graduate— and teacher—of the era. A 1948 commemorative anniversary booklet asserted it would “continue to be the policy of the administration...to have the College serve the southern part of New Jersey on the level of higher education with special emphasis upon preparing teachers for public school service."

Twenty-five years later, as the College—known as Glassboro State College—celebrated its 50-year anniversary, teacher education remained a major emphasis, but inroads were being made in new areas. In 1973, the College had three major academic divisions: Arts and Sciences, Fine and Performing Arts, and Professional Studies.

"We were primarily good at teacher education and we were just making moves in other directions with some other programs," said Don Bagin, then chair of the Public Relations/Advertising Department. The school was launching 15 undergraduate curricula including law/justice, Spanish, physical sciences, psychology and chemistry. "We were undergoing tremendous change to get these programs in place and develop and build a reputation for them."

"By then we were a multi-purpose institution," said Huston. "We had an influx of young people who were born as the result of the Second World War. So the College was booming and growing.

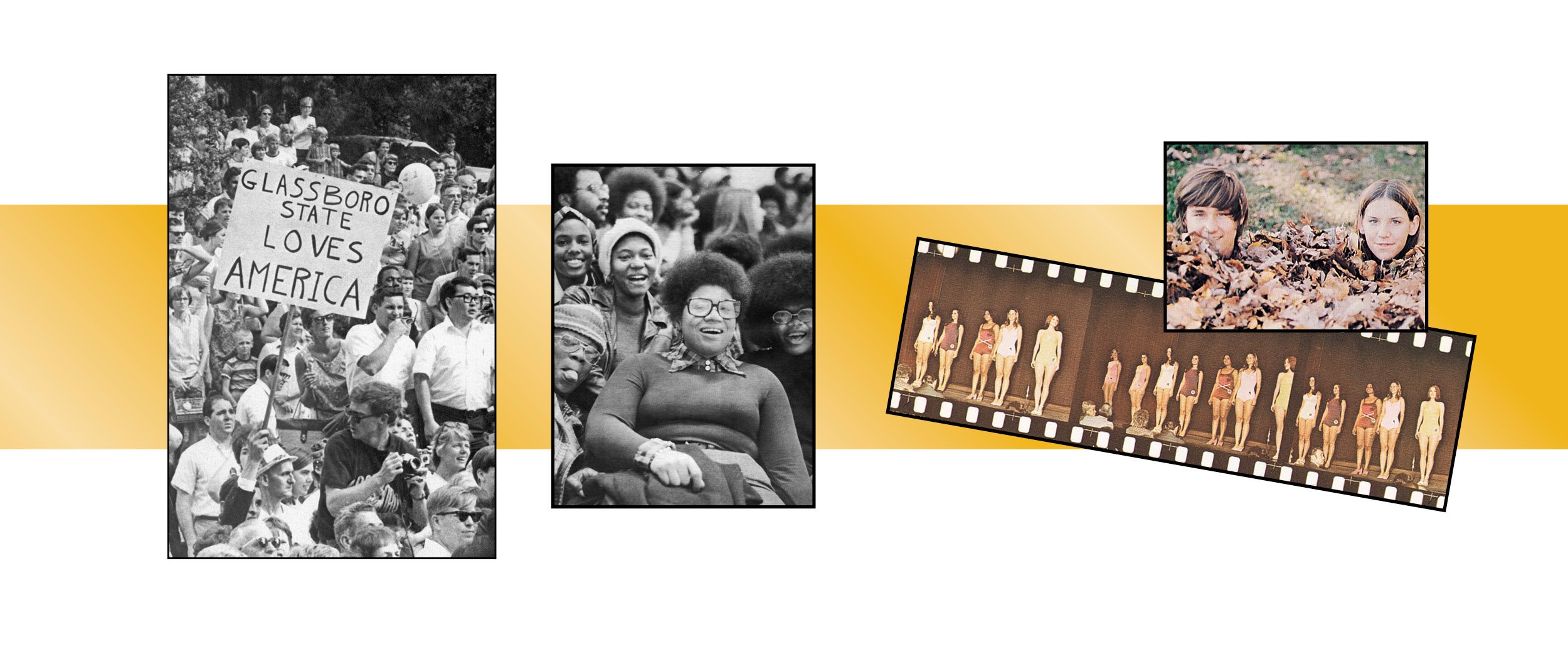

As in 1948, war once again claimed the focus of the nation in the 1970s. This time American troops were returning from Vietnam. Political issues also captured students' attention as The Whit asked: "Should Nixon Be Impeached and Removed from Office?" On a local level, students coped with a teachers' strike and urged state officials to reroute Route 322 because of its potential danger to campus pedestrians.

No longer were jackets and ties a concern at dinner—although student attire resurfaced as an issue when President Mark Chamberlain admonished the student body for instances of "streaking."

While some students chose to bare all, most chose to bundle up a little warmer as the energy crisis hit. Along with the rest of the nation, the College nudged down thermostats, reduced unnecessary lighting and encouraged car pools. Industrial arts students were assigned by professor George Samson to channel their creativity into solving this dilemma. They designed a monorail with a windmill-charged battery, a three-wheel electric car, and other energy-saving innovations.

Unlike Cook's experience in 1948, driving to Glassboro could mean encountering heavy traffic. "The biggest change in 25 years is getting here. With 295 and Rt. 55 open, it's much easier to get here," said Warren Binkley '73. "Before, the turnpike was quick, but it was a long trek down Delsea Drive or 322."

By 1973 the campus sprawled to cover the opposite side of Route 322, with more than 30 buildings on 181 acres. But more space was needed to accommodate the burgeoning enrollment of more than 11,000 full-time, part-time and graduate students. Binkley recalls the construction. "The current bookstore was the dining hall. We used to sit there and watch the piles driven and concrete poured for the new Student Center," he said.

By 1973 the campus sprawled to cover the opposite side of Route 322, with more than 30 buildings on 181 acres. But more space was needed to accommodate the burgeoning enrollment of more than 11,000 full-time, part-time and graduate students. Binkley recalls the construction. "The current bookstore was the dining hall. We used to sit there and watch the piles driven and concrete poured for the new Student Center," he said.

The College's golden anniversary year was marked by the dedication of the Wilson Music Building and the opening of the Student Center. Later, the Robinson Building opened in spring 1974 and existing buildings underwent renovations. The 50th Anniversary Mardi Gras Homecoming celebration and dinner dance was the first event held in the Student Center, which opened officially the following February. The Wilson Music Building was dedicated with the assistance of the renowned conductor of the Boston Pops Symphony. "Arthur Fiedler helped celebrate the dedication and he received an honorary doctorate," said Clarke Pfleeger.

Festivities held throughout the 1973-74 school year commemorating the anniversary included theatrical productions, concerts, and other events. Philip Sidotti '67, '73 designed a logo to commemorate the anniversary which proclaimed, "Glassboro State College: 50 Years of Educational Leadership." Distinguished Professor Robert D. Bole chronicled the five-decade history of the College in More Than Cold Stone. And to note the College's half-century of accomplishments, Congressman John E. Hunt introduced a resolution to the House of Representatives in recognition of the institution's service to the state of New Jersey.

Now, in 1998, the institution that began as Glassboro Normal School celebrates its 75th anniversary as Rowan University. About to leave the next quarter-century in his successor's hands, Rowan's fifth president, Herman D. James, reflected upon the school's history. "We have truly gone from Normal to extraordinary," he said.

Diane Donofrio Angelucci '81 is a freelance writer living in Clarksboro with her husband Dan Angelucci '75 and their two children.