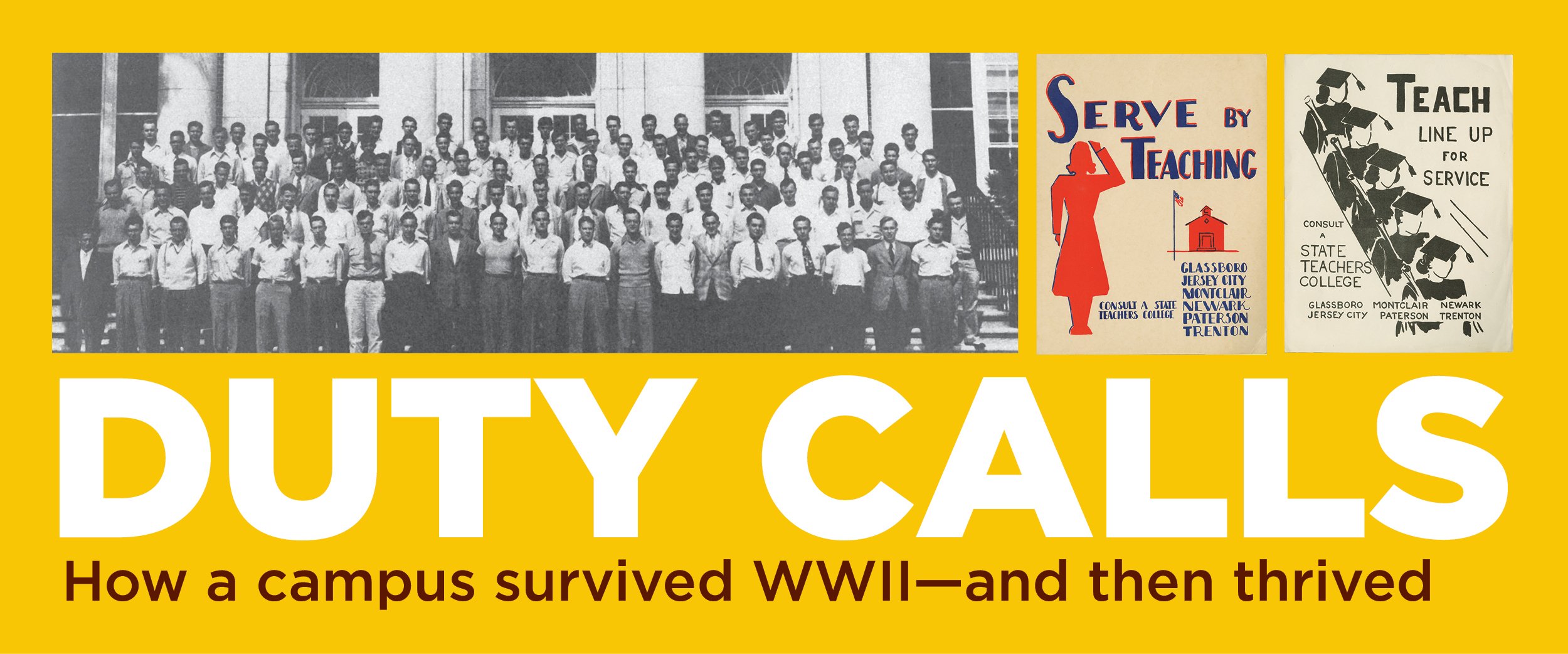

Students, alumni and faculty from the New Jersey State Teachers College at Glassboro fought battles of all kinds during World War II. In active war zones abroad, they confronted the Axis powers. In classrooms across South Jersey, they faced unrelenting teacher shortages.

During World War II, 201 Glassboro students and alumni—152 men and 49 women—served in the U.S. military. While two-thirds of these Glassboro students joined the Army, one quarter enlisted in the Navy. The remaining service members from Glassboro joined the Marines, Coast Guard and Nursing Corps. So many students went off to war that student enrollment at Glassboro declined by two-thirds, according to The First 25 Years in 25 Images: Photos and Film from 1923-1948.

Faculty members Samuel Witchell and Jay Carey served, too, in the respective roles of Navy officer and special-duty member of the Coast Guard.

Members of the Glassboro community fought on land, sea and air—and they made history.

Glassboro students and alumni fought in some of the most important battles of the war. Wesley Walton freed concentration camp prisoners, while Don Jess and Sam Porch liberated a Japanese prisoner-of-war camp.

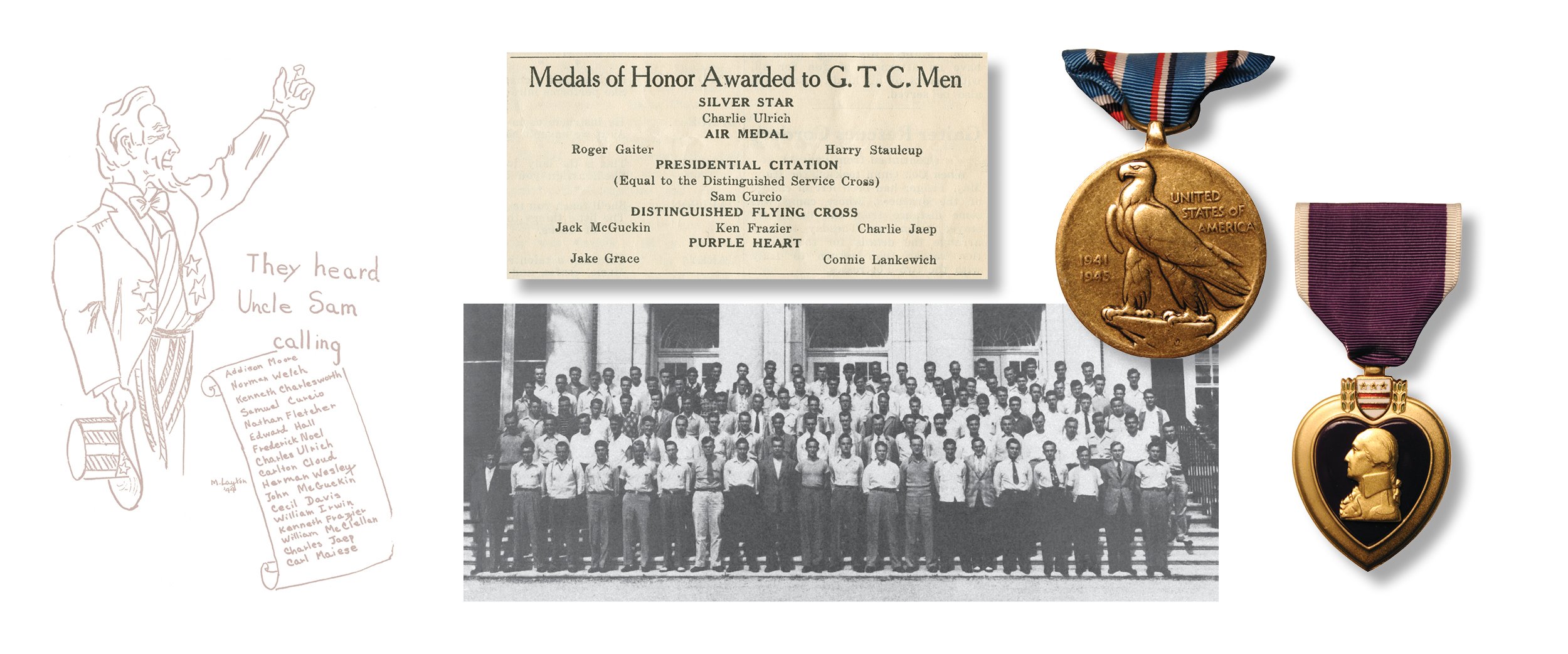

The contributions Glassboro students made to the war were notable. Harry Staulcup, for example, earned the Distinguished Flying Cross and the Presidential Citation for the 127 combat missions he flew during the war. Ken Frazier, part of the Marine Corps, won the Distinguished Flying Cross and the Navy Cross for shooting down 12 Japanese planes. Navy Lieutenant Charles Jaep won five air medals and the Silver Star for carrying out 26 torpedo-bomber attacks on Japanese warships and contributing to the first bombing of Tokyo.

Glassboro suffered losses, too. Those wounded in action included Edmund Cordery, Vyron Grace, Edwin Jacoby, Connie Lankewich, Harold Mickel, Clifford Moore and Frank Roesler.

Three Glassboro students and alumni gave their lives in the war. Addison Moore ’42 was shot down in the Pacific shortly before Japan surrendered. Jacob Moskowitz ’41, better known as Jack Morse, earned the Combat Infantry Medal and was promoted to first lieutenant in General George Patton’s Third Army before he was shot and killed in Germany. Flight Officer Benjamin Cummings ’45 was shot down during a mass raid over Germany.

For their sacrifices, all three were awarded Gold Stars.

World War II led to serious enrollment declines and changed life for the students who remained at Glassboro.

Faculty continued to teach and students continued to learn against the backdrop of blackouts and air raid drills. Materials rationing and unpredictable public transportation made even getting to campus difficult. The war and the threat of airstrikes extinguished the spotlight that had once illuminated the dome of College Hall (later known as Bunce Hall).

Intercollegiate sports were canceled. Publications of the yearbook were put on hold. Field trips became largely a thing of the past.

Classes and exams resembled normalcy, yet “Glassboro students devoted much of their time backing up the boys in the foxholes,” wrote Robert Bole, Glassboro State College administrator and historian, in his book “More Than Cold Stone.”

Donating blood, learning first aid techniques, knitting socks for soldiers and writing letters to service members replaced the pastimes students had enjoyed before the war. Some students served as air raid wardens or volunteered as USO canteen hostesses. A letter from Lt. John McGuckin to Glassboro faculty member Dora McElwain prompted a campaign to donate books for soldiers.

The faculty, too, turned their attention to the war and the hardships it created back home. Glassboro faculty members worked as air raid spotters and in wartime production factories, served on the local defense council and educated the public about the war.

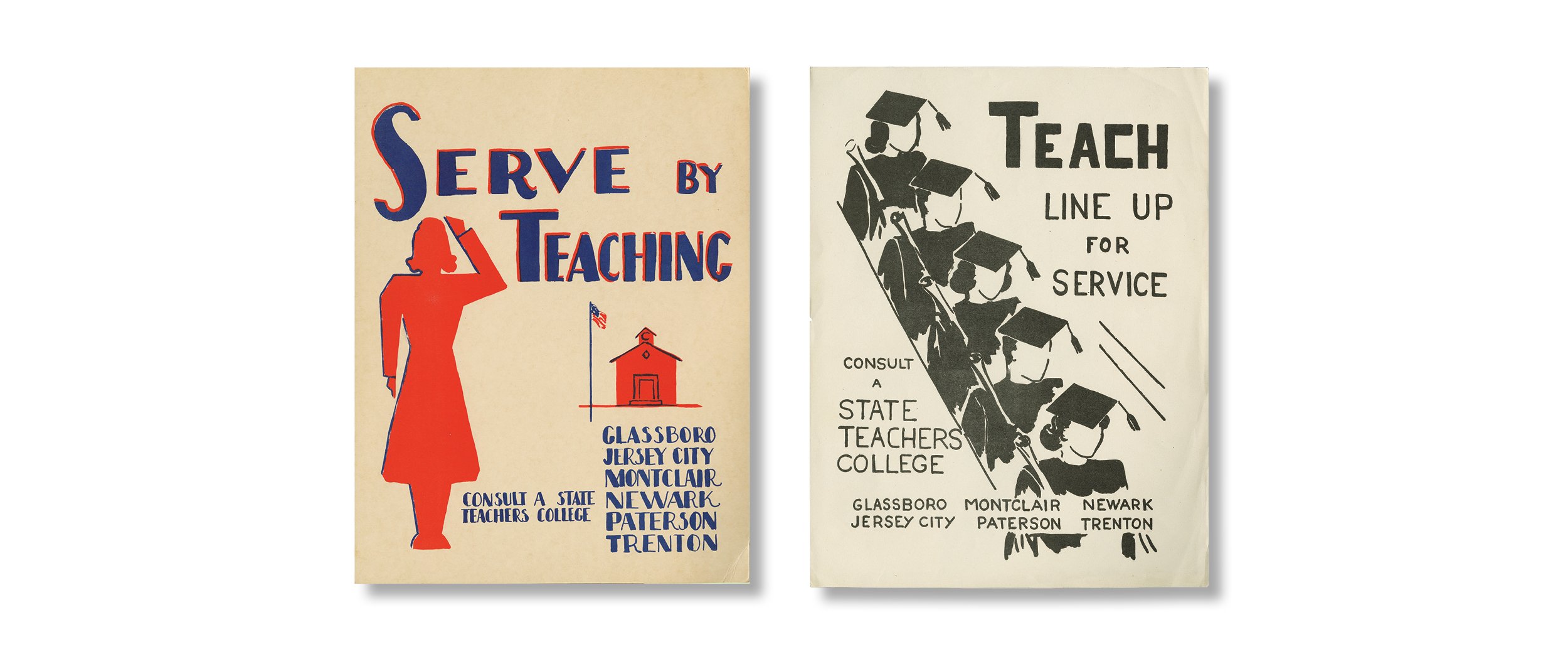

The remaining students at Glassboro faced immense pressure to finish their studies fast. The war gave rise to a dire teacher shortage in South Jersey and beyond. To produce classroom-ready educators faster, the college embraced an accelerated plan that allowed students to graduate a year early.

Even this sped-up preparation wasn’t enough to meet the worsening demands of the teacher shortage as the war wore on. The state Department of Education paved the way for college seniors to teach under emergency certification, which 36 Glassboro students did in February 1943.

Confronted by historically low enrollment numbers, the College’s president at the time, Edgar F. Bunce, “would sometimes deny military recruiters access to his students in an effort to retain aspiring teachers during the war years,” Bole wrote. Bunce explained this stance, saying, “I believe it is just as patriotic a duty to be a teacher of boys and girls,” according to Bole.

When the war finally ended in 1945, the College wasted no time seizing opportunities to rebuild and even expand. To accommodate the soldiers who returned from war, Glassboro created a junior college program that, for the first time, brought courses of study in fields like pre-engineering and business administration to the institution.

The College weathered the dark times of war and finally saw the enrollment growth, resources and energy necessary to resurrect its long-paused extracurricular activities and events. The post-war expansion permanently transformed the institution, preparing it for new growth in the decades ahead.