Written by:

Patricia Fortunato, Content and Program Manager, Clinical Research and Grants, NeuroMusculoskeletal Institute (NMI) at Rowan Medicine, Southern New Jersey Medication for Addiction Treatment Center of Excellence (MATCOE), Rowan–Virtua School of Osteopathic Medicine (Rowan–Virtua SOM); and

Gabby McAllaster, Ph.D. Candidate in Education at Rowan University and Doctoral Graduate Coordinator for Rowan University's Division of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI)

Originally written in March 2021, updated in March 2023

Women's History Month is rooted in the movements of socialism and labor. On February 28, 1909, in New York City, the Socialist Party organized the first "Woman's Day." The event paid tribute to the one-year anniversary of the garment worker's strikes in New York when thousands of women marched for economic rights through Lower Manhattan to Union Square. By 1911, Women's Day had launched an international observance across Europe. In the United States, according to the National Women's History Alliance, the Education Task Force of the Sonoma County, California Commission on the Status of Women focused on the issue of history books' omission of women's contributions and in 1978 hosted "Women's History Week," a celebration of women's contributions to history, culture, and society similar to the United Nations' International Women's Day which launched in 1975. In 1979, one of the Women's History Week organizers, Molly Murphy MacGregor, attended a conference with the Women's History Institute at Sarah Lawrence College and shared the success of Women's History Week in Sonoma County, inspiring a celebration across the nation. Organizers lobbied Congress and President Jimmy Carter proclaimed the first National Women's History Week for March 2–8, 1980.

The Women's National History Alliance lobbied for a longer observation, and Congress passed a proclamation in 1987 establishing Women's History Month.

Terms and Language Guidance for Continued Learning

- Black Feminism: Black feminist consciousness is the recognition that African American women are status deprived as they face discrimination as a result of the intersection of race and gender. Black feminists advocate for Black women who bear the burden of prejudice that challenges people of color, in addition to the various forms of subjugation that hinder women.

- Feminism: Generally seen as the advocacy of the social, political, and economic equality of all genders. There are many types of feminism.

- Intersectionality: A theoretical concept describing the interconnection of oppressive institutions and identities.

- Misogyny and Trans-Misogyny: Misogyny is a general hatred and hostility towards women. Trans-misogyny is the same hatred, targeted at trans-feminine people.

- Sexism: A system of beliefs or attitudes which regulates women to limited roles and/or options because of their sex. It centers on the idea that women are inferior to men.

- Sexual Harassment: According to the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, "Harassment can include sexual harassment or unwelcome sexual advances, requests for sexual favors, and other verbal or physical harassment of a sexual nature. Harassment does not have to be of a sexual nature, however, and can include offensive remarks about a person's sex. For example, it is illegal to harass a woman by making offensive comments about women in general. Both victim and the harasser can be either a woman or a man, and the victim and harasser can be the same sex."

- Sexual Assault: Unwanted sexual contact or threat.

- Consent: A mutual and enthusiastic agreement between sexual partners. Partners can revoke consent at any time. Consent cannot be legally given while a sexual partner is intoxicated.

- Rape: According to the U.S. Department of Justice, "penetration, no matter how slight, of the vagina or anus with any body part or object, or oral penetration by a sex organ of another person, without the consent of the victim."

- Rape Culture: A culture in which sexual assault is common and maintained by attitudes about sexuality and violence.

- Survivor vs. Victim: Debated terms focused on how to identify those who experience crime; usually, sexual assault. Some use survivor as a way to empower those who have lived through an experience, while others believe that it should be a chosen title.

- Victim Blaming: Victim blaming occurs when victims/survivors are silenced, shamed, and/or held responsible, even partially, for a crime. It is critically important to affirm victims/survivors and avoid statements including and not limited to, "Don't think about it," "Why didn't you leave?," and "Why didn't you fight back?"

- Title IX: Title IX is a federal civil rights law passed as part of the Education Amendments of 1972. This law protects people from discrimination based on sex in education programs or activities that receive Federal financial assistance.

Important Figures to Women's History

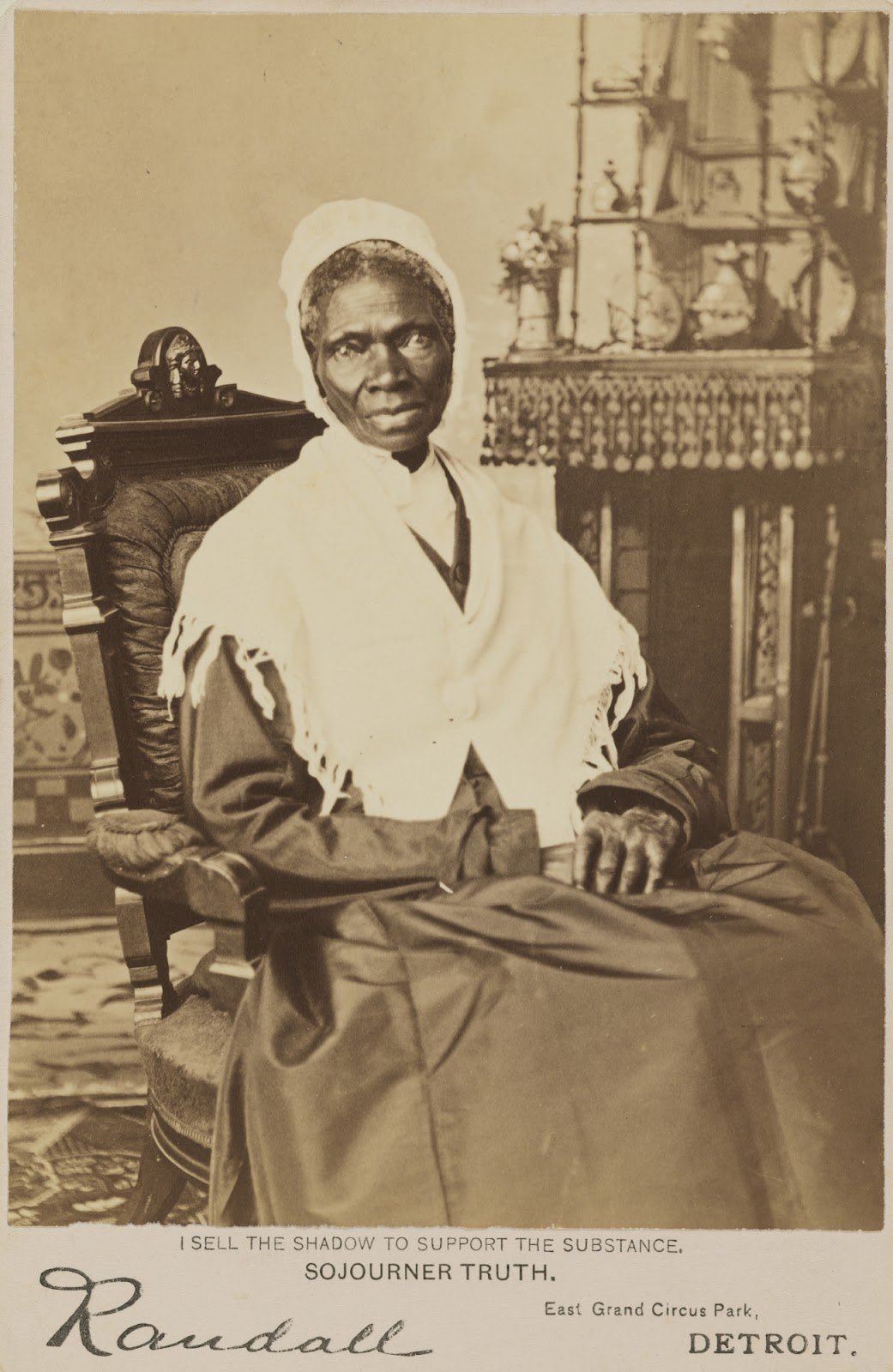

Sojourner Truth (1797–1883) was born Isabella Baumfree in Ulster County, New York, in 1797. She was traumatically separated from her family and enslaved several times, further suffering sexual and physical abuse by slave masters. Her first language was Dutch, and she learned to speak English, which served her well in her eventual career as an orator. She had one son and four daughters, and prior to New York abolishing slavery on July 4, 1827, she escaped with her infant daughter. After her escape, she learned that her son was illegally sold and enslaved, and she went on to successfully sue for custody. In 1828, she moved to New York City and became a preacher in the Pentecostal Church. She adopted the byname "Sojourner Truth" in 1843, speaking out against racial injustices and gender-based violence. She is most known for her speech "Ain't I a Woman?" at the Women's Rights Convention of 1851 in Akron, Ohio. The speech responded to male ministers' rhetoric discriminating against women's rights.

Truth is celebrated for her commitment to intersectionality. She recognized the varying injustices that people with multi-identities can face—a stark contrast to the beliefs of Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, who refused to support the Black vote if it wasn't also granted to include women.

Photograph via the National Portrait Gallery

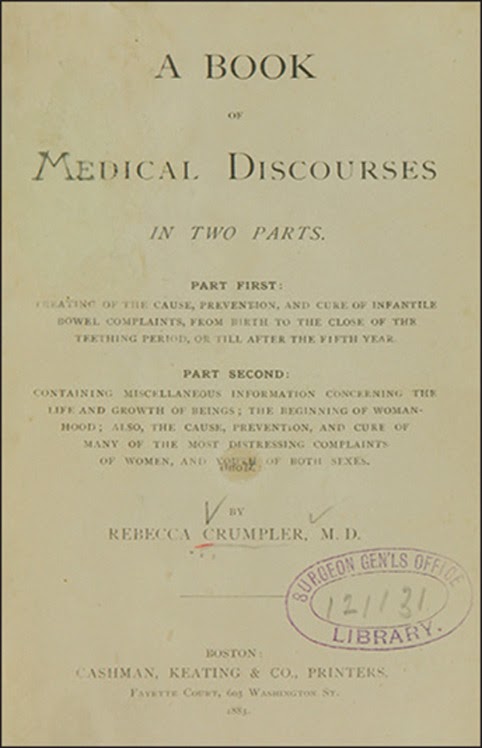

Dr. Rebecca Lee Crumpler (1831–1895) was born in Delaware and raised by an aunt in Pennsylvania who cared for sick neighbors, who may have inspired her trailblazing career. In 1852, she relocated to Charlestown, Massachusetts, and as the nation’s first nursing school did not open until 1873, she was able to perform nursing work without formal training and work as a nurse for eight years. Thereafter, in 1860, she enrolled in the New England Female Medical College. The College was founded by Drs. Samuel Gregory and Israel Tisdale Talbot in 1848, and accepted its first class of twelve women in 1850. Other male physicians disparaged the College, arguing that women could not master medical curriculum. In 1864, Dr. Crumpler graduated from the New England Female Medical College as the first African American woman in the U.S. to become a Doctor of Medicine.

It is critical to note that in 1860, there were 54,543 physicians in the U.S., of which 300 were women, and none of the physicians were African American. She went on to practice medicine in Boston before relocating to Richmond in 1865 parallel to the end of the Civil War to practice missionary medicine, describing that experience as "a proper field for real missionary work, and one that would present ample opportunities to become acquainted with the diseases of women and children. During my stay there nearly every hour was improved in that sphere of labor. The last quarter of the year 1866, I was enabled . . . to have access each day to a very large number of the indigent, and others of different classes, in a population of over 30,000 colored." In 1869, she and her husband returned to Boston where she continued to practice medicine, before relocating to Hyde Park, New York in 1880 and publishing A Book of Medical Discourses in Two Parts in 1883.

Dr. Crumpler died on March 9, 1985. Let us celebrate her achievements and legacy, especially as an inspiration to all women medical students and physicians who are experiencing adversity and discrimination. The current physician workforce does not reflect the diversity of the U.S., especially concerning gender and race. As of 2019, 51.1% of the U.S. population identifies as female and 12.9% of the population identifies as Black and female, while as of 2020, 37% of practicing physicians are women and recent data indicates that just 2% of physicians are Black women. The underrepresentation of women and BIPOC in medicine is a critical issue spanning academia, the physician workforce, and patient outcomes, and must be met with progressive recruitment, retention, inclusion, and promotion.

Cover scan via The Lancet

There are no known verified photographs of Dr. Crumpler available.

Dr. Susan La Flesche Picotte (1862–1915) was born on the Omaha Reservation in Nebraska, the daughter of Chief Joseph La Flesche (Iron Eyes) and Mary La Flesche (One Woman). She attended the Elizabeth Institute for Young Ladies in New Jersey before returning to the Omaha Reservation when she was 17, to teach at the Quaker Mission School. As a child, she bore witness to a white physician refusing to provide care for an ill Native American woman, and later cited this experience as inspiration to become a physician. While teaching at the Quaker Mission School, she attended to the health of the ethnologist Alice Cunningham Fletcher, who in turn urged her to attend medical school. She went on to complete her education at the Hampton Institute, now named Hampton University, a historically Black research university in Hampton, Virginia. The institution's resident physician, Dr. Martha Waldron, encouraged her to apply to her alma mater, the Women's Medical College of Pennsylvania. Fletcher helped her achieve scholarship funds during this time, from the U.S. Office of Indian Affairs and the Women's National Indian Association sub-branch of the Connecticut Indian Association.

She completed her three-year program at the Women's Medical College of Pennsylvania in two years, graduating in 1889 as the first Native American woman in the U.S. to become a Doctor of Medicine. She went on to complete her medical internship in Philadelphia and returned to Omaha to provide medical care for 1,200 individuals at the government boarding school. She married her husband in 1894 and went on to set up a private practice in Bancroft, Nebraska, raise two sons, care for her husband while he was terminally ill, and opened a hospital in the reservation town of Walthill, Nebraska, in 1913.

Today, the building remains open as a museum dedicated to Dr. Picotte and the history of the Omaha and Winnebago tribes.

Photograph via the Dr. Susan La Flesche Picotte Center

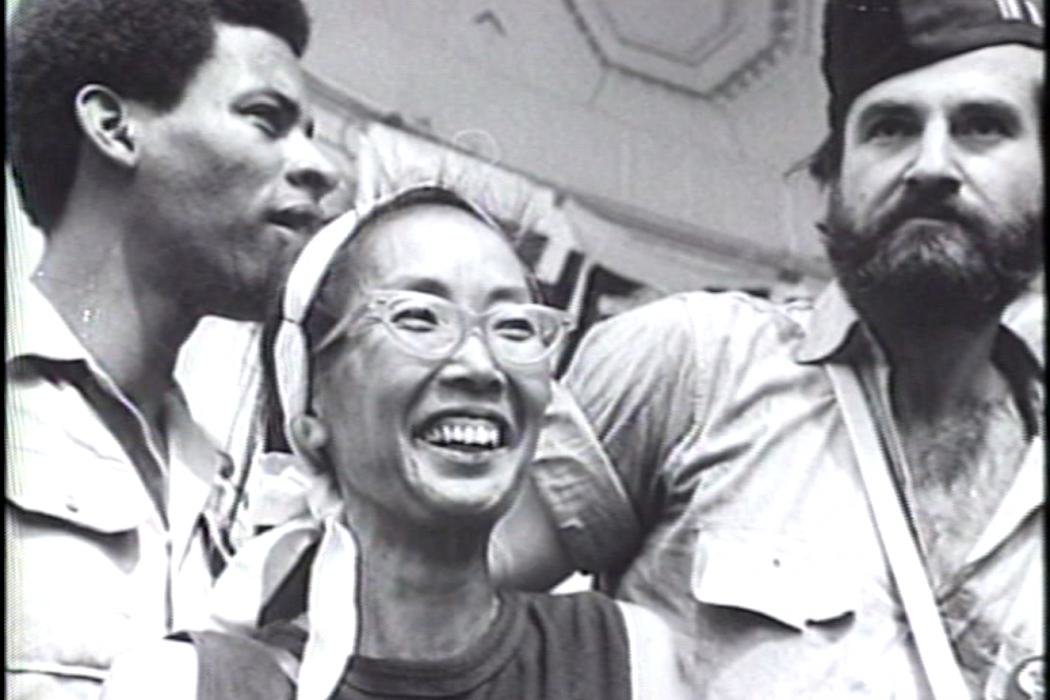

Yuri Kochiyama (1921–2014) was born Mary Yuriko Nakahara in San Pedro, California. After the Pearl Harbor tragedy, she and her family were incarcerated in the internment camps with 120,000 other Japanese Americans. During this time, she met her husband at an internment camp in Arkansas. They married after World War II and lived in Harlem, New York City, in housing projects among Black and Puerto Rican neighbors, inspiring her passion for the civil rights movement and leading her to host weekly open houses for activists in her family's apartment. She and her family spent time learning about Black history at the Harlem Freedom School, part of a grassroots organization dedicated to advocacy for safety and integrated education.

Also in Harlem, she met and befriended Malcolm X in 1963. Their friendship was brief but formative in helping radicalize her activism, as she began focusing her work on black nationalism. She was with Malcolm X minutes after he was murdered during his last speech in New York City in 1965 and in an interview with Miya Iwataki for KPFK Pacifica Radio in 1972, she said of him, "He certainly changed my life. I was heading in one direction, integration, and he was going in another, total liberation, and he opened my eyes."

She was a member of the Young Lords Party, a political action group for Puerto Rican independence, and participated in the storming of the Statue of Liberty in 1977. Further, she and Chinese American activist Gloria Lum co-founded Asians for Mumia, a group advocating to free Mumia Abu-Jamal, a radio journalist, and Black Panther convicted and sentenced to death for the murder of a Philadelphia police officer in 1981. She protested against the Vietnam War and imperialism, joined labor organizing, and advocated for the compensation of formerly incarcerated Japanese Americans.

Her lived experiences with incarceration in internment camps influenced her deep commitment to anti-racism and anti-imperialism, and her empathy for Arabs, South Asians, and Muslims experiencing racial profiling post-9/11. In September 2001, at a San Francisco Bay Area peace vigil, she called upon her fellow Japanese Americans to "Remember Pearl Harbor" as Arab, South Asian, and Muslim sisters and brothers were the "newest targets of racism, hysteria, and jingoism."

In Kochiyama's interview with musician and composer Fred Ho in Legacy to Liberation, Revolutionary Worker, she shared a strong statement, excerpted below.

"I've spoken to kids as young as second and third graders. A school here in Harlem — the teachers were both Black and white, but the students were all Black — asked if I would come and speak to them about Malcolm X. And I couldn't believe how much these second and third-grade students already knew about Malcolm. But it was because their parents knew about Malcolm. And I've spoken to junior high schools, one in Greenwich Village. I've spoken to about six high schools and to colleges all over the country, and the enthusiasm and interest of the students, regardless of what age, has amazed me. And it's been very, very heartening. They really are interested. They really want to change society. They want it to become a better society than they are living in now.

What I would say to students or young people today. I just want to give a quote by Frantz Fanon. And the quote is 'Each generation must, out of its relative obscurity, discover its mission, fulfill it or betray it.'

And I think today part of the missions would be to fight against racism and polarization, learn from each others' struggle, but also understand national liberation struggles — that ethnic groups need their own space and they need their own leaders. They need their own privacy. But there are enough issues that we could all work together on. And certainly support for political prisoners is one of them. We could all fight together and we must not forget our battle cry is that 'They fought for us. Now we must fight for them!'"

Still from Yuri Kochiyama: Passion for Justice, a 1993 film by Rea Tajiri and Pat Saunders

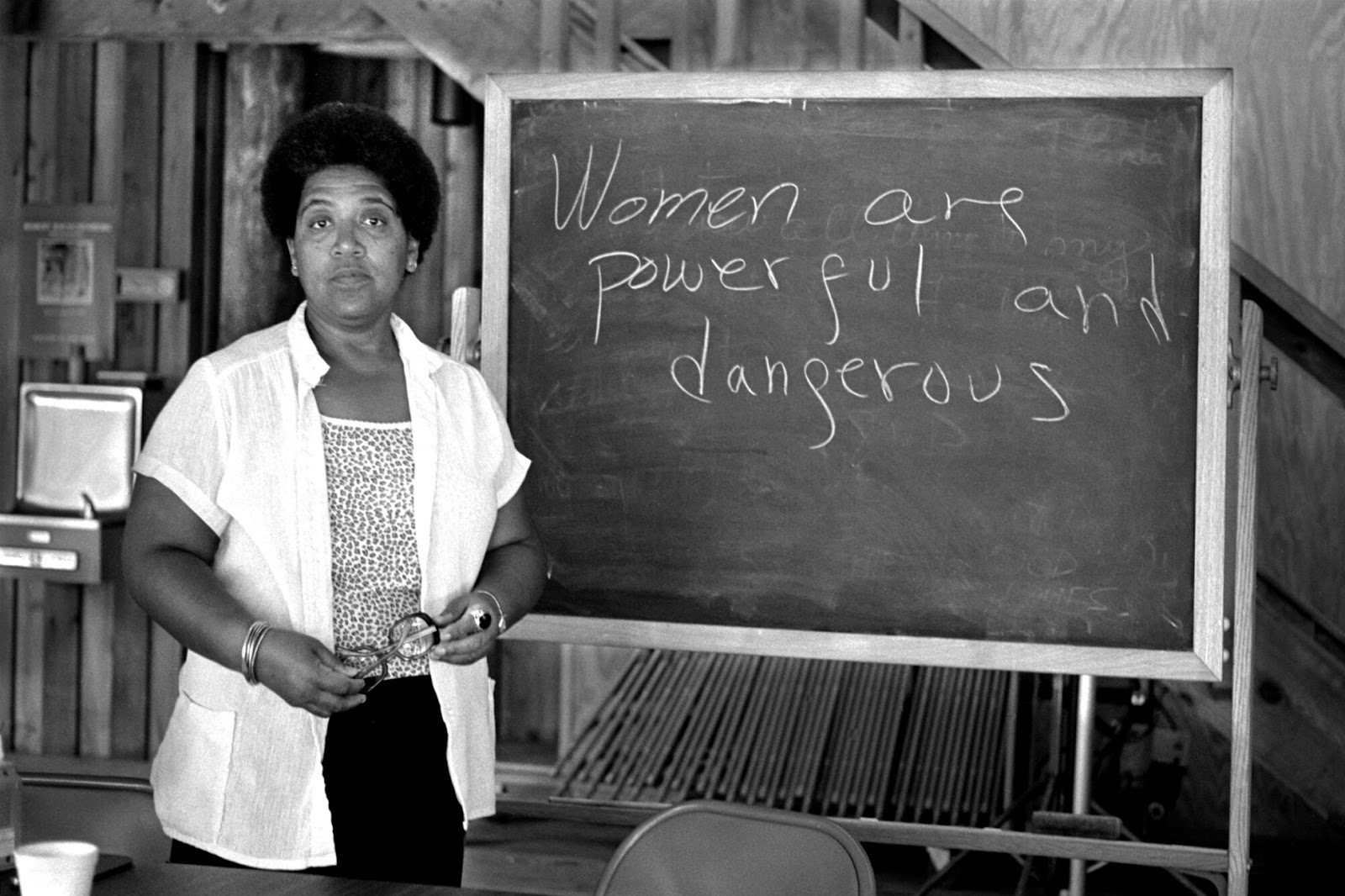

Audre Lorde (1934–1992) was born in New York City, the daughter of West Indian immigrants. Self-described as "black, lesbian, mother, warrior, poet," Lorde dedicated her life to bravely confronting and working to eradicate issues of racism, sexism, homophobia, and classism. She attended Catholic elementary school and Hunter High School, and while still a high school student, she published her first poem in Seventeen magazine. She went on to earn her Bachelor of Arts from Hunter College and Master of Library Sciences from Columbia University and was a librarian in the New York City public school system in the 1960s. She and her husband had two children prior to divorce in 1970. She went on to meet her partner, Frances Clayton, in 1972. Her work and life were informed by her exhaustive experiences with pedagogy and teaching; as a Black, queer woman in white academia; and her groundbreaking contributions to critical race studies and feminist and queer theory.

Lorde is celebrated for her essays summarizing the intersections of race, gender, and class, including "The Master's Tools Will Not Dismantle the Master's House" and "The Transformation of Silence into Language and Action." The latter essay was delivered at the Modern Language Association's "Lesbian and Literature Panel" in Chicago on December 28, 1977, and first published in Sinister Wisdom 6 in 1978 and The Cancer Journals in 1980, excerpted below.

"And where the words of women are crying to be heard, we must each of us recognize our responsibility to seek those words out, to read them and share them and examine them in their pertinence to our lives. That we not hide behind the mockeries of separations that have been imposed upon us and which so often we accept as our own. For instance, 'I can't possibly teach Black women's writing — their experience is so different from mine.' Yet how many years have you spent teaching Plato and Shakespeare and Proust? Or another, 'She's a white woman and what could she possibly have to say to me?' Or, 'She's a lesbian, what would my husband say, or my chairman?' Or again, 'This woman writes of her sons and I have no children.' And all the other endless ways in which we rob ourselves of ourselves and each other.

We can learn to work and speak when we are afraid in the same way we have learned to work and speak when we are tired. For we have been socialized to respect fear more than our own needs for language and definition, and while we wait in silence for that final luxury of fearlessness, the weight of that silence will choke us.

The fact that we are here and that I speak these words is an attempt to break that silence and bridge some of those differences between us, for it is not difference which immobilizes us, but silence. And there are so many silences to be broken."

Photograph via The Poetry Foundation

Justice Sonia Sotomayor was born in 1954, in the Bronx to Puerto Rican parents and raised in a housing project. Her father was a factory worker and died when she was nine, while her mother, a nurse, raised her and her younger brother. She found comfort in books (particularly, Nancy Drew books) as a child, which inspired her love of learning and led her to a career in law. She developed a relentless work ethic and a deep dedication to her studies, graduating as valedictorian of her classes at Blessed Sacrament School and Cardinal Spellman High School in New York. She was awarded a scholarship and attended Princeton University where she graduated summa cum laude and Phi Beta Kappa with a Bachelor of Arts in history. After graduating, she married Kevin Edward Noonan, with whom she had been in a relationship with since high school. She went on to Yale Law School, where she served as an editor of the Yale Law Journal, managing editor of the student-run Yale Studies in World Public Order now known as the Yale Journal of International Law, and co-chaired a group for Latin, Native American, and Asian students.

Her former classmate, Robert Klonoff, shared his memory of her with the Washington Post in 2009, "She would stand up for herself and not be intimidated by anyone. I think she'd be the kind of justice who could change some minds." She graduated from Yale Law School with her Juris Doctor in 1979 and was hired as an assistant district attorney under New York District Attorney Robert Morgenthau the same year. She worked 15-hour days, gaining a reputation for her work ethic and preparedness.

She and Noonan divorced amicably in 1983, and she went on to house an informal solo law practice in her Brooklyn apartment where she performed legal consultations. In 1984, she entered private practice. On November 27, 1991, she was nominated by President George H. W. Bush for a seat in the U.S. District for the Southern District of New York, thus becoming the youngest judge in the Southern District, the first Hispanic federal judge in New York State, and the first Puerto Rican woman to serve as a judge in a U.S. federal court. She went on to be nominated by President Bill Clinton for a seat in the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit.

On May 26, 2009, President Barack Obama nominated her to the Supreme Court, culminating in her confirmation by the full Senate. Justice Sotomayor is the first Hispanic to serve on the Supreme Court, and one of five women to have ever served on the Court.

Supreme Court Justices Sandra Day O'Connor (who is not wearing a robe as she is retired from the Court), Sonia Sotomayor, the late Ruth Bader Ginsburg, and Elena Kagan.

Photograph by Steve Petteway, photographer for the Supreme Court of the United States, and available in the public domain.

Ways to Support and Center Women

Promote intersectionality. Intersectional feminism recognizes the overlapping and complexities of identities, such as race, gender, sexuality, class, etc., and challenges systems that uphold power and privilege. Intersectionality originates from Black feminists, such as Sojourner Truth, Audre Lorde, and bell hooks, who critiqued both feminism—which traditionally focused on white women's issues—and civil rights movements that considered race but did not consider gender. Therefore, Black feminists brought an understanding and lived experiences of the multi-layered systems of oppression.

In 1989, legal scholar and civil rights activist Kimberlé Crenshaw coined the term intersectionality. Crenshaw's well-cited scholarly critique, Mapping the Margins, examines antidiscrimination theory and how in practice, it fails Black women by denying that they face unique discrimination due to their overlapping identities. Intersectionality critically highlights the multiple identities within the identity "woman" which need to be considered. Furthermore, intersectionality is an analytical tool to disrupt systemic inequity and oppression towards liberation for all marginalized and minoritized identities.

Advance trans-inclusive feminism. Advancing women's equity means recognizing and supporting the historical role and the ongoing advocacy of all diverse women, including trans/non-binary identities. Historically, the trans community has been excluded from women's and feminist spaces and movements. A fundamental tenet of feminism seeks to end forms of oppression, which therefore, must include advancing equity and inclusion for trans people. Trans artists, scholars, and activists have contributed vastly to feminist movements and theory.

Feminist activist and organizer Laura Kacere wrote the following for Everyday Feminism in 2014.

"Our struggle should not focus only on making the feminist movement more inclusive — this is about making trans people and other marginalized members of the feminist movement a central part of it.

We can't just call out transphobic attitudes — we have to allow trans people a non-tokenized voice and space in our movement.

In her book Excluded: Making Feminist and Queer Movements More Inclusive, Julia Serano states, 'We all have a mutual goal: to find a support network outside of the hetero male-centric mainstream where we can finally feel empowered and affirmed as women.' Our goal thus becomes, she notes, building communities that celebrate difference rather than sameness, where everyone is listened to, where everyone is seen as a legitimate object of desire, where gender expressions and presentations are not policed, and where trans women are not viewed as less legitimate than cis women.

We have to recognize trans women as women (and include them in women's spaces!), recognize trans men as men, and recognize genderqueer and non-binary identifying people as being outside of or in between those categories, defined by their own experiences and expression on the gender spectrum."

Remove sexist language from your vocabulary. Historically, language has held the pretense that men should hold the power in systems and society. A few examples of sexist language include and are not limited to "hey guys," "act like a lady," "man up," "chairman," and any words that imply that being a woman is less than. The use of gender-exclusive language reinforces harmful stereotypes and runs the risk of misgendering or invalidating a person's identity. The way in which we speak and communicate with our loved ones, colleagues, and students matters.

In academia, often women—especially women of color—are not referred to with their formal titles such as "Dr.," Dr. Nichole Margarita Garcia explains, "When your first response is not to call me 'Dr.' in an academic setting, you erase not only me, but the generations before me."

There are many other examples of women experiencing invalidation in academia and we all must be aware of the language that we are using every day, and strive to create and foster environments in which all people feel respected, valued, and validated.

Lastly, creating a welcoming and inclusive environment includes taking meaningful action against sexism, racism, xenophobia, and all intolerant speech both in-person and online. Strive to be an upstander and discourage others from engaging in such behavior. To report an act of discrimination, contact the Office of Student Equity and Compliance.

Create environments for women to take up space. Be mindful of how you celebrate women's achievements, and recognize the very prevalent issue of men both interrupting women and stealing women's ideas. You should be earnest in how you express value to all colleagues and students. Be honest with yourself and examine biases that you may hold. For example, science faculty (irrespective of gender) tend to view male students as more competent than equally qualified female students. Similarly, recommendation letters for postdoctoral fellowships display significant gender differences that favor male applicants. Utilizing an intersectional lens, research showed that standard course evaluations are often biased against faculty who identify as women of color, and research also showed that transgender people are often dramatically underrepresented in academia.

Overcoming implicit biases against women and transgender identities requires an explicit effort to promote women and trans/non-binary people in the workplace. When planning manuscripts, include women, especially women of color, as authors. When writing manuscripts, cite women, especially women of color. When planning subject matter expert panels, consider the diversity of the panels. When in meetings, consider your identities and how you may be taking up space instead of adding to a space.

Resources for Continued Learning

Websites:- Everyday Feminism is "an educational platform for personal and social liberation."

- Equal Rights Advocates is a nonprofit legal organization dedicated to protecting and expanding economic and educational access and opportunities for women.

- The Center for Changing Our Campus Culture is an online resource to address dating violence, domestic violence, and sexual assault, supported by the Department of Justice's Office on Violence Against Women.

- The National Domestic Violence Hotline provides tools and immediate support to enable victims to find safety.

- The National Women's Law Center works to protect and advance the progress of women and girls in school and at work, with special attention given to the needs of low-income women and families.

- BetterBrave is a guide to identifying and addressing sexual harassment, discrimination, and retaliation in the workplace.

- Me Too is a movement that supports survivors of sexual violence and their allies by connecting survivors to healing resources, and offering community organizing resources, information regarding pursuing a "me too" policy platform, and sexual violence research.

- Rise is a multi-sector coalition of sexual assault survivors and allies working to empower all survivors with civil rights and in 2016, drafted and passed the Sexual Assault Survivors' Bill of Rights unanimously through Congress.

Articles:

- Riggio, O. (2020). 'Hey Guys,' It's Time to Take Gendered Language Out of Your Vocabulary. DiversityInc.

- Humphrey, K. (2020). Trans Rights Have Been Pitted Against Feminism, But We're Not Enemies. The Guardian.

- Aparna, R. (2020). The Burden and Consequences of Self-Advocacy for Disabled BIPOC. Disability Visibility Project.

- Solnit, R. (2014). Why #Yesallwomen Matters. Mother Jones.

Videos:

- TED. (2016, December 7). The Urgency of Intersectionality | Kimberlé Crenshaw [Video]. YouTube.

- TEDx Talks. (2013, April 12). We Should All Be Feminists | Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie | TEDxEuston [Video]. YouTube.

Books:

- Miller, C. (2020). Know My Name: A Memoir. Penguin Books.

- Wong, A. (Ed.). (2020). Disability Visibility: First-Person Stories from the Twenty-First Century. Vintage.

- Kendall, M. (2020). Hood Feminism: Notes from the Women that a Movement Forgot. Viking.

- Gay, R. (2019). Bad Feminist. HarperCollins.

- Ekall, P. Y. (2019). Taking Up Space: The Black Girl's Manifesto for Change.

- Gay, R. (2017). Hunger: A Memoir of (My) Body. HarperCollins.

- Taylor, K. Y. (Ed.). (2017). How We Get Free: Black Feminism and the Combahee River Collective. Haymarket Books.

- Serano, J. (2016). Whipping Girl: A Transsexual Woman on Sexism and the Scapegoating of Femininity. Hachette UK.

- Suzack, C., Huhndorf, S. M., Perreault, J., & Barman, J. (Eds.). (2010). Indigenous Women and Feminism: Politics, Activism, Culture. UBC Press.

- hooks, b. (1996). Teaching to Transgress: Education as the Practice of Freedom. Journal of Leisure Research, 28(4), 316.

- Davis, A. Y. (1989). Women, Culture & Politics. Vintage.

- Lorde, A. (1984). Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches. Penguin Classics.

- Davis, A. Y. (1981). Women, Race & Class. Vintage.

Online Bookstores:

- Harriett's Bookshop is a Black woman-owned shop named for Harriet Tubman, that celebrates women authors, artists, and activists.

- Bluestockings is a collectively-owned bookstore powered by volunteers, with selections ranging from race studies, prison abolition, class and labor, trans fiction, Indigenous studies, Black feminism, and more.

- Cafe con Libros is an intersectional feminist bookstore owned by Kalima DeSuze, an Afro–Latinx woman veteran and social worker.

- For Keeps Books features rare and classic editions by Black authors. A handful of special titles, often rapidly selling out, are available through the website.