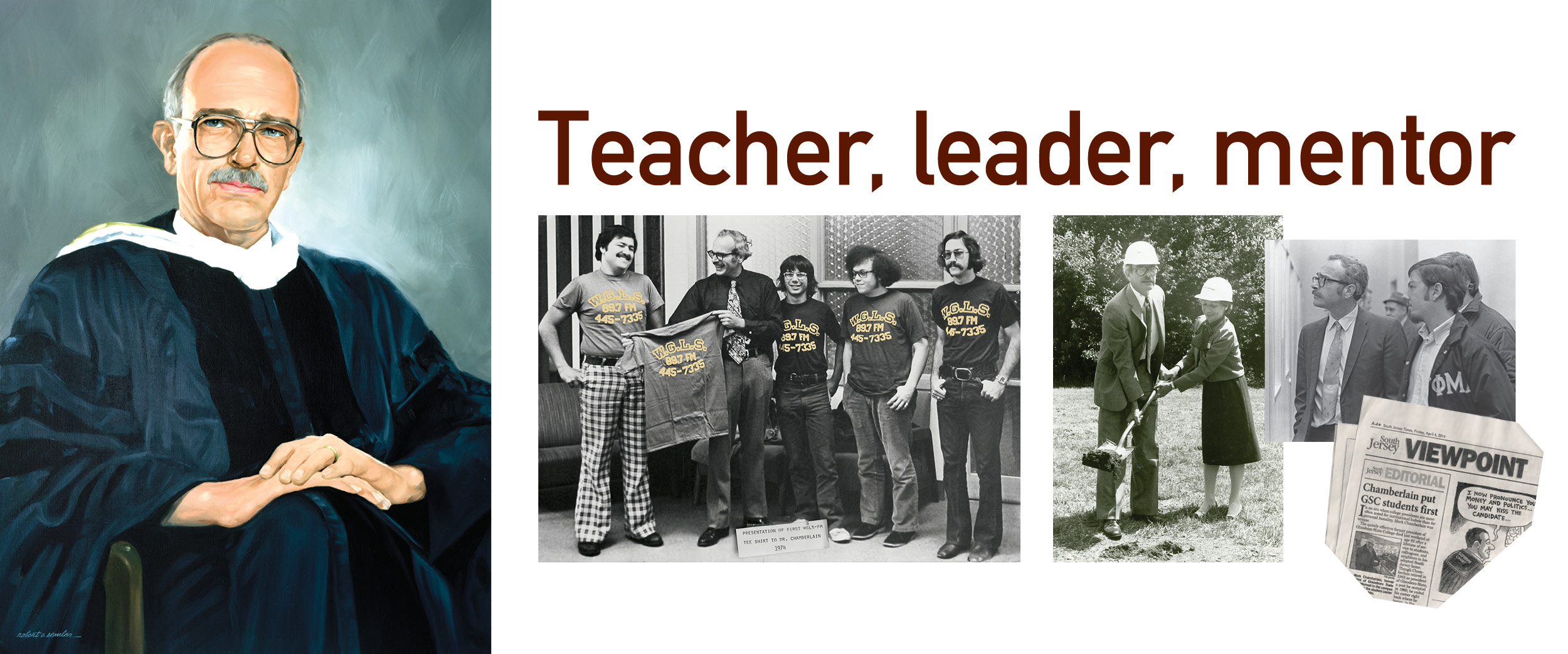

You might think that the legacy of Mark M. Chamberlain, Rowan University’s fourth president, would be the sweeping changes implemented under his watch—new landmarks like Wilson and Robinson halls, the Student Center, which was later named in his honor, and a vision that transformed then-Glassboro State College from a well-regarded teachers school to one that educates a wide range of professionals.

And, to a great extent, you would be right.

But Chamberlain, who died March 29 after a heart attack, leaves a legacy even greater than that.

Just 38 when he was hired, Chamberlain led GSC from 1969 to 1984—a tumultuous period not only on campus but also across America.

Hired from Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland where he began his teaching career in the department of chemistry and rose to vice provost for student affairs, he brought a sense of calm and vision to GSC that served the institution well during his tenure and set it on a course for greatness.

In a relatively short period, he supervised the development of three new academic divisions and encouraged the start of a dozen major programs, two educational specialist programs and a score of minors, specializations and concentrations. Full-time enrollment more than doubled, from 3,529 in fall 1968 to 8,788 in fall 1984, and the number of on-campus residential students increased from 900 to more than 2,700.

To accommodate this student influx, nine buildings were built or purchased and another five extensively renovated.

Chamberlain also helped students gain new privileges in academic policy and campus life. Minority student enrollment increased appreciably, as did the number of women and minorities among the faculty and administration. College-employee relations were considered to be among the best in the state college system and the Faculty Senate became a strong and viable governing body.

Chamberlain’s vision of developing GSC into a diverse regional institution laid the foundation for the school’s evolution into what it is today—New Jersey’s second comprehensive public research university.

But it’s doubtful Chamberlain would have described it that way.

“He was, in many ways, a very humble man,” said Robert Newland, professor emeritus in the department of chemistry and biochemistry and a colleague and friend of Chamberlain’s since 1983. “He was dedicated to the students and that’s one reason the board hired him to be president in the first place.”

Newland said he and Chamberlain had much in common, from their love of teaching to a passion for chemistry to a fascination with the Civil War, in particular the Battle of Gettysburg, and battlefield ordnance’s reliance on chemicals.

He said it amused Chamberlain when, after some 15 years in the President’s Office, he moved to a space in Bosshart Hall that was so tight he could spread his arms and touch two parallel walls.

“It was pretty small, especially coming from the president’s suite, but it didn’t bother him at all,” Newland recalled.

Newland and others said despite Chamberlain’s meteoric academic career, what always impressed them was his kindness for others—students, junior faculty, even complete strangers.

He believed in service to the community and, upon settling in Glassboro, became a volunteer firefighter who was known to bolt from meetings to answer the wail of a fire alarm.

“When he was advising or mentoring junior faculty he never expected any return,” said Cathy Yang, a professor in the department of chemistry and biochemistry who, hired in 1995, had an office near Chamberlain’s and Newland’s.

“Purely from his heart he wished for people to be successful,” Yang said. “If he saw a spark in faculty, particularly in junior faculty, he would encourage you to pursue your dream.”

Like many professionals, academics who rise to management positions do not often return to their starting places, but Chamberlain’s f irst and last love was teaching.

Barbara Chamberlain ’88, his wife of 26 years, said he relished those times when a difficult lesson hit home.

“When students had that ‘a-ha’ moment, he really just loved it,” she said. “He used to say that when he went back to the faculty he got a promotion. He loved being a teacher.”

Decades ahead of Rowan Boulevard, the massive construction project linking Rowan’s main campus with Glassboro’s historic downtown, Chamberlain knew that the institution and borough must overcome difficult town/gown relations that plague many campuses and their host communities.

“He felt there needed to be a strong connection between the college and the community and for that I think he was a visionary,” she said. “He somehow could look ahead and see where things were headed.”

Friends, colleagues and former students agree that Chamberlain’s innate gift of diplomacy and compassion helped GSC prosper at a time when America was in crisis and campuses from coast to coast were riven by protest, uncertainty and violence.

He was challenged early in his presidency when, in 1970, President Richard M. Nixon approved sending troops into Cambodia, an escalation of the Vietnam War.

But Chamberlain, who had been hired in part for his background in diplomatically guiding student affairs at Case Western Reserve, didn’t disappoint when the possibility of a student strike surfaced that May. He formed a committee of students, faculty and administrators and devised a plan some called the Glassboro Compromise of 1970, which would permit the College to remain open but also allow the more activist students and faculty to express their opinions.

Students were given options: attend classes, use the semester to pursue peace-seeking goals, complete courses through independent study, take an incomplete grade, withdraw or be marked based on work completed to date.

Students and faculty accepted the plan and the crisis was averted.

“One of his great gifts was inspiring calmness,” Barbara Chamberlain said. “His nature was calming and sincere and students would come and talk to him.”

David Burgin ’82, president of the Rowan University Alumni Association, met Chamberlain toward the end of his presidency when, as a reporter for The Whit, he began interacting with him.

Burgin said part of Chamberlain’s appeal was his natural inclination to be out and about with students, faculty and staff, walking—or running—all over campus.

“This was a time when students were still leery of leadership but we were always comfortable with him,” Burgin said.

And Chamberlain was fast on his feet. When U.S. Rep. Millicent Fenwick was unable to make it to campus for the 1982 Commencement, Chamberlain gave a moving ad hoc address.

“Dr. Chamberlain just stepped right in and took care of it,” Burgin said of the reliable president.

“He was very confident and self-assured and when he made a statement you knew it was going to get done,” he said.

Ric ’80 and Jean ’81 Edelman said Chamberlain’s influence on them as students and graduates cannot be overstated.

“There are only a handful of people who have truly influenced our lives and Mark Chamberlain is one of them,” said Jean Edelman. “We were both active in student government and Dr. Chamberlain’s guidance and mentoring was priceless to our development as leaders.”

The couple founded Edelman Financial Services, one of America’s largest independent investment and financial planning firms.

Among many fond memories the Edelmans recalled was Chamberlain co-piloting an earthmover on Earth Day 1980 and taking a call on his private home phone late one night after a disturbance broke out at Mansion Park Apartments.

“Dr. Chamberlain has helped to make us who we are, and we cherish our memories of him,” said Ric Edelman.

Chamberlain, 83, held a bachelor’s degree in chemistry from Franklin & Marshall College and a Ph.D. in chemistry from the University of Illinois. After announcing in October 1983 that he would step down from the presidency and return to teaching, he was named distinguished professor of chemistry. He taught until his retirement in June 2000 and remained active on campus after leaving the classroom.