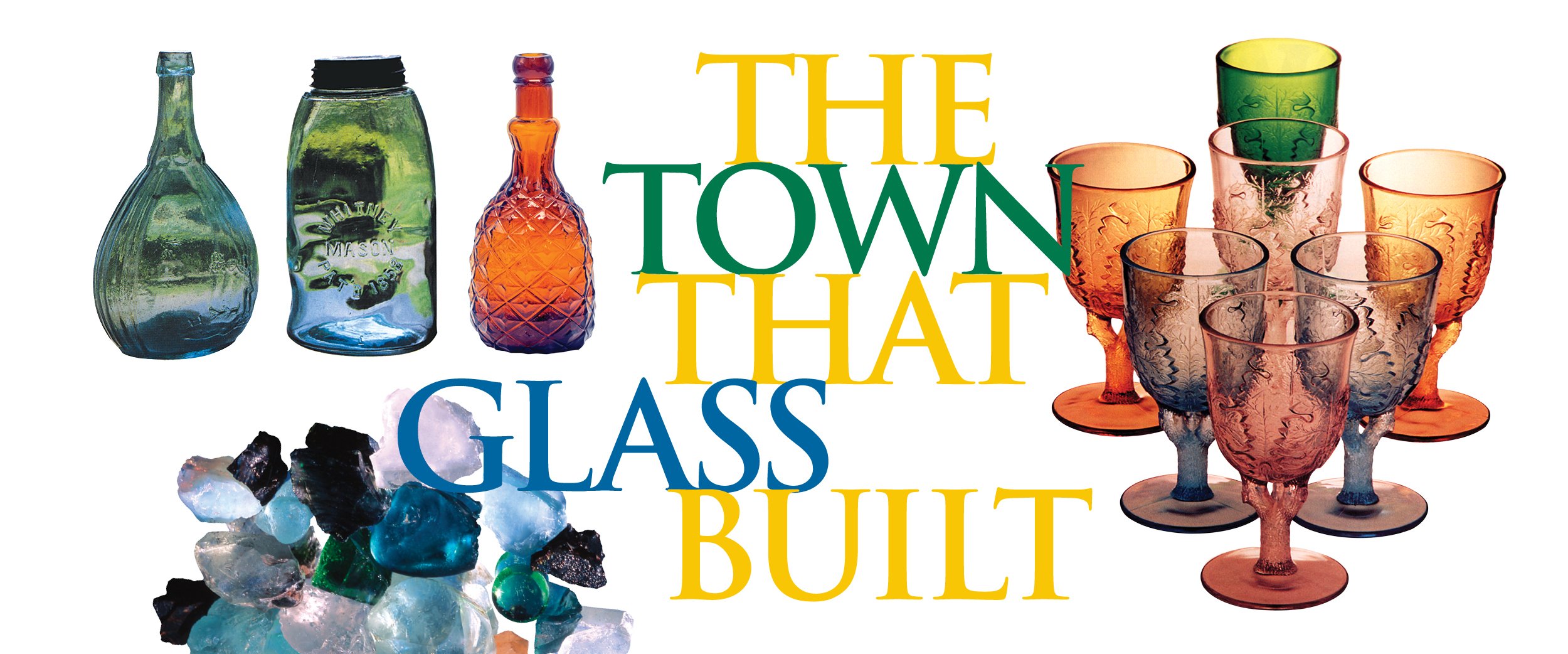

Bits of colored glass sparkle in the sunlight along the paths of the old quad. Smooth as pebbles, thicker than shards, this is glass cullet—hardened scraps of molten glass, refuse from the first and finest glass-producing industry in early America. At the height of production in the late nineteenth century, hundreds of skilled artisans created utilitarian bottles and one-of-a-kind pieces of art on the 12-acre Whitney Glass Works, the center of a thriving community. Today, where massive furnaces glowed and smokestacks plumed, museums and memories honor Glassboro's history. Marilyn Plasket '50, president of the Board of Trustees of the Heritage Glass Museum, is a descendant of early glassblowers. "Long before it was a college town, Glassboro was a 'glass town,'" she says, citing the fortuitous combination of art, industry and business that founded an industry, built a town and established a college.

The late Professor Emeritus Robert Bole's book The Glassboro Story is the definitive history of Glassboro. Bole states that the first European settlers, the Stanger family, came to this remote area from Dornhagen, Germany, in 1775 to make and sell glass. Founding a "glassworks in the woods," the Stangers were attracted here by excellent sand as a raw material, abundant oak trees to fuel furnaces, and proximity to the port of Philadelphia for exporting glass products throughout the colonies and into Europe. Political conditions worked against the Stangers, however. The Revolutionary War and the devaluation of Continental currency caused the glassworks to fail in 1781.

"The Stangers were tremendous glassblowers," says Plasket, "but they weren't very good businessmen. Their property was sold at a sheriff's sale to Revolutionary War heroes Thomas Carpenter and Colonel Thomas Heston, who had served under George Washington at Trenton. They successfully reopened the Stanger operation, naming it the Heston-Carpenter Glass Works.

According to Bole, it was Heston who gave Glassboro its name. Under his stewardship, the glassworks prospered as did the surrounding area. Workers built homes and reared families near the factory; soon, churches, schools, shops and taverns sprang up in the village. "The story goes that when Colonel Heston went to the annual fox hunting club banquet, members told him that his place had grown into a respectable-sized village and needed a proper name. They suggested Glassborough, and the Colonel agreed. Today, we have the distinction of being the only Glasssboro in the United States," added Plasket.

In 1806, sea captain Eben Whitney, who sustained injuries in a shipwreck off Cape May, reached shore and headed to Philadelphia for medical treatment. He only got as far as Glassborough, where he fell in love and married Bathsheba Heston, the Colonel's daughter. Although Whitney knew nothing about glass, he gave up the sea and put his energies into expanding the family business.

In 1835 Bathsheba and Eben's sons, Thomas and Samuel, changed the name of the factory to Whitney Glass Works. Expanding the business, the Whitneys bought hundreds of acres of timberland to fuel the furnaces. Ultimately, their extensive holdings brought great wealth, as the town prospered and neighboring farms and villages were settled.

"The Whitneys had tremendous influence not only in Glassboro but throughout the nation. They had contacts with congressmen, senators, perhaps even a president or two. Thomas and Samuel Whitney were astute, powerful businessmen who shaped the town's future," added Plasket.

During the decorative excess of the mid-Victorian period, fancy Whitney bottles were all the rage; the glassworks produced the Jenny Lind flask, the "Booz'' whiskey bottle (creating the slang term booze), and inkstands in the form of bee hives, log cabins and cider barrels. The buildings were continually refurbished and expanded to meet the growing demand for Whitney products.

"The Whitney brothers' Glass Works were the most extensive and best equipped in the country; their products were known nationally. Because the Whitneys encouraged creativity, their glassblowers produced some of the era's most beautiful glass products. We are fortunate to have some of their pieces on display at the museum," added Plasket.

In 1849, returning from a European holiday, the Whitneys built a mansion that was the talk of Glassboro. Set in a wooded deer park named Holly Bush, the 26-room brownstone had the distinction of being the first house in the region to have running water.

For the next 30 years, the Whitneys produced utilitarian medicine bottles and flasks along with one-of-a kind "whimsies."

In the late 1870's, when the glass industry was at its peak, Thomas and Samuel retired, turning over day-to-day operations to John Whitney and Thomas Whitney Synnott, a nephew who was to have a profound influence on the future of the College.

In 1904, Michael Owens' automatic bottle-making machine, which had taken six years and $300,000 to develop, went into experimental production. The Whitneys bought one machine in 1910, and by 1912 had five machines operating, putting 130 glassblowers out of work.

A few years later, after a disastrous fire had destroyed much of the old glassworks, a new automated glass factory opened on Sewell Street, and the Whitney name began to disappear from letterhead and advertising, replaced by the name Owens.

"In 1920 the last melt was made in the Whitney factory and a short time later the old Whitney Glass Works in the center of town was torn down. Now, the Owens automated bottle factory that replaced the Whitney Glass Works has closed, having made its final product in March," commented Plasket.

But the Whitney legacy didn't end with the demise of the glassworks; instead, it opened another chapter in Glassboro's history. In 1917 the Normal School Committee of the State Board of Education began looking for a site for the new South Jersey normal school.

One committee member was prominent Glassboro resident, Thomas Synnott, former president of the Whitney Glass Works and president of the Glassboro National Bank. Synnott had a reputation for taking charge and getting things done. He presented a strong case for locating the new normal school in Glassboro, citing its central location, closeness to the railroad and natural beauty.

"People from neighboring communities accused Synnott of having a financial interest in locating the school in Glassboro; after all, the site he suggested was owned by the Whitney family," says Plasket. But Synnott, like his ancestors, was a shrewd businessman. He knew the state needed a desirable site for the new school, and his family's land was available at a fair price. He also saw an opportunity to bring a new source of employment to the community, adds Plasket.

Meanwhile, 107 civic-minded Glassboro residents were doing their part to locate the school in their town. They raised $6,500, enough to buy 25 acres of the Whitney estate, which they offered to the state free of charge. The committee also recommended that the state purchase an additional 30 acres of the Whitney tract at a cost of $16,000.

By December the state had clear title to the 55-acre Glassboro site and the famed Whitney mansion. Even after the decision was made, Synnott did not abandon his commitment to the project. He arranged to have all the original buildings on the site cared for, at no expense to the state, until the new school was opened six years later.

"Although the Stangers, Hestons, Carpenters, Whitneys and Synnotts have melted in the fabric of our past, their contributions to Glassboro remain," says Plasket. "The Stangers founded our glass industry. Heston and Carpenter were its financial saviors. And the Whitneys, with their business savvy, brought the industry to its greatest heights."

Hollybush, the Whitney mansion, now serves as the official residence of College presidents and a living memorial to its builders. In 1967, the mansion achieved international fame when, during the waning days of the Cold War, College president Thomas Robinson invited Lyndon Johnson and Soviet Premier Aleksei Kosygin to meet at what came to be known as the Hollybush Summit.